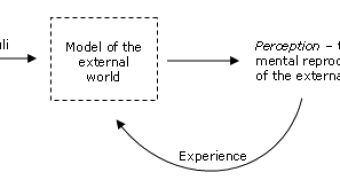

Researchers in cognitive psychology have started to study how magic tricks work in an attempt to obtain clues about the details of perception. When we perceive something we don't just see it as it is. In fact, the process of perception is a complex cognitive process during which our brain creates a mental reproduction of the external world based in part on the clues obtained from the sense organs, in part on our past experience and in part on genetically transmitted perception mechanisms (a genetically determined expectation of how the world is).

Psychologists are interested in the details of this mental model of the external world. What kinds of stimuli does it use and in what ways are the stimuli used? The study of magic tricks and of optical illusions offers a window into this.

"It made sense to look at magicians to advance knowledge of human cognition, since magicians have been working on figuring out how certain principles of psychology work for hundreds of years," said Gustav Kuhn from the University of Durham in England, a cognitive psychologist who has also performed magic the past couple decades. "Magicians really have this ability to distort your perceptions, to get people to perceive things that never happened, just like a visual illusion."

Researchers started with a relatively simple magic trick: the vanishing ball. The magician throws a ball into the air several times and at one point the ball seems to disappear. Kuhn filmed himself doing the trick, first in the proper way - that fools about two thirds of the people watching it - and second in an improper way - that only fools about one third of observers. See the movie from Live Science.

The ball doesn't really disappear, but the magician simply keeps it in his hand while mimicking the gesture of throwing the ball into the air. The proper way of doing the trick, the thing that fools the audience, is to follow with your eyes the non-existing ball's fly into the air. If you look at your hand instead, the audience is less likely to be fooled.

Kuhn and his colleagues measured the eye movements of volunteers watching him doing the trick. They found that people believed they were watching the ball while actually they were watching the magician's gaze. In other words, the volunteers were not even conscious that they weren't really looking at the ball!

"Even though people claimed they were looking at the ball, what you find is that they spend a lot of time looking at the face. While their eye movements weren't fooled by where the ball was, their perception was. It reveals how important social cues are in influencing perception," Kuhn said.

The reason why we give so much importance, even unconsciously, to other people's gaze is that this usually offers a reliable clue to their intentions. And it seems that the social inputs into that model of the external world, such as the clues about other people's intentions, are more important than the actual visual stimuli. Moreover, the model produces our perception not only based on the received stimuli and on the social clues, but also on what it is expected to happen. The brain deals with the otherwise overwhelming complexity of the visual input by relying on its own predictions of what should happen and not only on what actually happens.

"As we are looking at the world, we have this impression that what we see is the real world," Kuhn explained. "What this tells us is the way we see the world is more strongly dominated by how we perceive it to be rather than what it actually is. Even though the ball never left the hand, the reason people saw it leave is because they expected the ball to leave the hand. It's the beliefs about what should happen that override the actual visual input."

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //