When you look around you, you see a three-dimensional world. But how is this possible? The brain does not interact directly with the world, it gets its data from the two images of the world that form on the retina of your eyes. But these images are two-dimensional. How does the brain create the sensation of three-dimensionality from these two images?

The answer in more complicated than you might think. The hasty answer is that the visual areas of the brain act like a sort of computer that recreates the three-dimensional world from the differences between the two retinal images (see image, credit: Rachel Cooper). And after the three-dimensional world is recreated mentally it is sent to some other area of the brain that interprets everything (that classifies the objects).

One simple way of proving the importance of two eyes in creating the 3D sensation is to close one eye and to try to slowly approach your two index fingers trying to touch them. Your fingers will probably be slightly misaligned because the brain isn't entirely successful in figuring out the position of your hands (and fingers) in the 3D space. Thus, the differences between the two retinal images are indeed useful.

But they are far from being the whole story. Why don't you err even more when you close one eye? You can obtain an interesting clue about this question by doing the following experiment proposed by Tim Hunkin.

Research on visual perception at Cambridge University has found that without the 'visual clues' of the T.V. surround the eye can see a very convincing 3D picture. All is needed to create this effect is a bit of cardboard cut as indicated (the hole in the middle is the same proportions as the screen but 10% smaller). Simply view screen through hole placing yourself so you can't see the edges of the screen. Credit: www.rudimentsofwisdom.com

What happens? You are watching an actual 2D image, but your brain recreates it mentally as a 3D space. It is clear that the 3D sensation doesn't "simply" recreate what you see by doing some computation. In fact, it can be proven mathematically that the information you get from the two retinal images is insufficient for recreating the 3D space.

Think about a simple example: when you look at a square painting from one side, the image of the painting on the retina is not a square. There are many possible shapes seen under many possible angles that can produce the two retinal shapes. Nonetheless, the brain makes a very definite choice. And it seems to be very certain of what it sees.

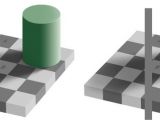

This particular image reveals the fact that perception involves a choice: the brain decides the tiles are squares and therefore you see a wavy 3D image instead of a two-dimensional one. There's nothing in the image itself that points to the idea that the tiles are squares. This is something the brain has added cheerfully.

The two steps involved in visual perception - the recreation of the 3D space and the interpretation - are more intertwined: interpretation helps the mental recreation of the objects. When you realize that this is as a snake you suddenly see it more clearly against the background. In the Hunkin experiment you see the TV image as 3D because you have a certain everyday experience of 3D objects and when the brain uses this experience it manages to recreate mentally more than it is actually there.

Optical illusions are possible precisely because the interpretation processes are involved in the recreation of the objects. Moreover, they offer insight about precisely how interpretation is involved.

It's interesting to look at such illusions and to try to determine what underlining assumptions are used by the process of perception. Why does a particular illusion happen?

For example, why do you get such a powerful impression that the horizontal lines in this image are not parallel? The answer is that such images are not encountered very often in the real world and the brain has difficulties making sense of it. It tries to make the image look more familiar by modifying the horizontal lines.

In the example above the tiles A and B are of the same color. Why do they look different? It seems that our brain doesn't "just see" the color of something. It deduces the color and one factor involved in this deduction is the appearence of the surrounding objects. Paradoxically, this doesn't happen because our brains are dumb; on the contrary, it happens because they are, and they have to be, much smarter than we might realize it.

The brain has to deduce the color of something irrespective of illumination. This used to be vital for our ancestors because color reveals all sorts of important information. For example it reveals whether a fruit is ripe or not.

In order to account for illumination while determining the color of something the brain has to look at the relative colors of various objects. But that isn't sufficient. The brain needs to identify the objects, or at least to partially identify them, in order to have a clue about their possible colors. In the illusion above the brain identifies tile B as a "white" tile because of its position and it infers that it has to be of a different color than tile A - which has been identified as a "black" tile due to its position - and due to the color of other tiles nearby.

This image, as well as many other ambiguous images, shows that the underlining assumptions of our perception are not just geometrical or concerning colors - they also involve our interests. What have you seen first? The woman or the musician? Is that surprising?

Starting with such examples about perception we can wonder and speculate about the involvement of expectations and interests in other more complex processes. For instance do we really observe other people for what they are? How often are we blinded by our expectations and interests and replace the real people with a sort of complex optical illusions?

Some studies have shown that we're doing it much more often than we think. But in such cases it seems much more difficult to identify the underlining assumptions. Why do we create these illusions? While perceptual illusions (illusions regarding objects) happen as side effects of our otherwise very clever brain, psychologists usually argue that the illusions regarding other people serve certain purposes (such as protecting our self-image). Is that really so?

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //