Primates are the only mammals with the ability of seeing colors. Scientists have wondered for sometime what was the initial benefit of this evolutionary advance. One hypothesis was that this helped them spot ripe fruits or nutritional leaves. But then, why didn't other mammals developed color vision?

Color vision is made possible by the cone cells in the retina. In order to get some idea about what might have been the initial purpose of color vision, scientists determined to which wave-lengths primates cone cells are most sensitive.

This wasn't exactly easy. "Basically, careful retinal neurophysiologists and psychophysicists spent untold numbers of hours measuring how sensitive each cone is to each wavelength of light," says Mark Changizi at Caltech in Pasadena, California.

Changizi and colleagues also charted how hemoglobin's color varied with or without oxygen. They found that the difference was most evident at around the light wavelengths of 540 and 560 nanometers. In fact, this was already common knowledge for a long time as it is the basis on which optical biosensors for the measuring of blood-oxygen levels are built.

Nonetheless what the team found to be very interesting was that the cone cells most sensitive to these particular wavelengths belonged to primates with the most advanced color vision, such as humans and gorillas. Thus, it appears that color vision developed in order to spot the differences between oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

Such differences are often the result of emotion: the blushing is caused by an increase in oxygenated blood. This suggests that primate's color vision may have evolved to pick up on these physiological changes below the skin's surface. In other words, our eyes may have evolved partly to pick up on cues such as blushing.

Changizi also noted that primates with more advanced color vision tend to be bare faced: "Much more recently, evolutionarily speaking, some primates evolved the ability to see these spectral modulations of the skin, and there was probably a co-evolution between fur-loss on the face or rump."

There is only one problem with this entire study. Other studies have shown there is a huge variability in the structure of the retina: some people have more cones sensitive to red, others to green. The sensation of color is created mostly by the brain and not by the cone's structure. Thus, it appears they have only come across a coincidence and not a causal connection: the cones they painstakingly studied just happened to be most sensitive to the wavelength of around 540-560 nanometers. If they were to study the cones from many more people (and probably other primates too) they wouldn't have found the same coincidence.

Nonetheless, their hypothesis about why color vision evolved seems very interesting, but unfortunately their study doesn't do much for proving it.

[The idea that the primates are the only mammals with color vision isn't entirely correct either - but it is true that most mammals don't have color vision.]

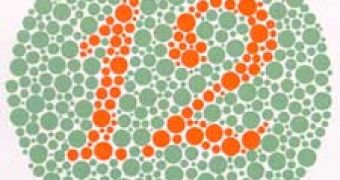

Image: a test for detecting color vision defects

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //