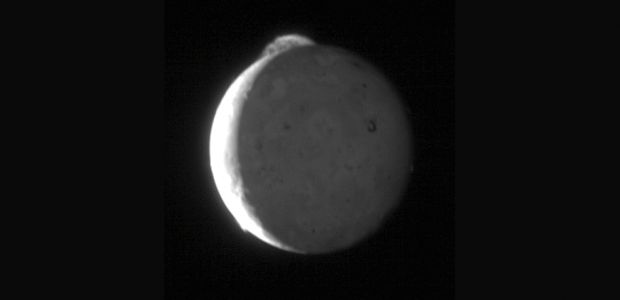

There's an army of active volcanoes on the surface of Io, the innermost of Jupiter's four Galilean moons. No, really, there are hundreds of them and some are in the habit of spewing out fountains of lava up to 250 miles (around 400 kilometers) tall.

The reason Io is the most geologically active orb in the Solar System is that its place in the sky makes it vulnerable to Jupiter's gravity, but also to the occasional gravitational pull from Europa, another of the planet's Galilean moons.

Gravitational pulls from Europa force Io to follow an oval orbit. In turn, this means the orb flexes when moving around Jupiter. The result is that material inside it constantly readjusts. This friction produces heat, which goes on to fuel geological activity.

“Io orbits faster, completing two orbits every time Europa finishes one. This regular timing means that Io feels the strongest gravitational pull from its neighbor in the same orbital location, which distorts Io's orbit into an oval shape,” NASA scientists explain.

“This modified orbit causes Io to flex as it moves around Jupiter, causing material within Io to shift position and generate heat by friction, just as rubbing your hands together briskly makes them warmer,” they go on to detail.

When studying the distribution of active volcanoes across Io's surface, however, scientists found that the fiery mountains didn't quite line up with where friction was supposed to generate the most intense heat. Rather, most of them were 30 to 60 degrees more to the East than expected.

A possible explanation

Quite puzzled by this topographical quirk of Io, researchers ran some more models. They now think that this moon of Jupiter appears to have its volcanoes in the wrong place because of a hidden ocean of magma.

Such a molten rock ocean hidden in the moon's underground and its influence on surface geological activity would explain the distribution of volcanoes on Io, they say.

In a recent report in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, researcher Robert Tyler explains how, having completed and studies a series of simulations, he and his colleagues found that tidal heating from such an ocean would birth the topography already observed on Io.

Previously, Io was thought to be a perfectly solid orb, albeit a deformable one, kind of like a lump of clay. This new study, however, suggests that its anatomy might, in fact, be more complex than assumed.

“We found that the pattern of tidal heating predicted by our fluid-tide model is able to produce the surface heat patterns that are actually observed on Io,” explains scientist Robert Taylor.

If it is true that Jupiter's moon Io hides a magma ocean, this means other orbs similar to it might too have bodies of fluids, be it molten rock or water, lurking under their crust.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //