Modern research is delivering loads of information, and proper experts are having trouble dealing with this so-called data deluge. The solution: enlist the help of citizen scientists ready and willing to devote some of their time to advancing our knowledge of the world we live in.

One citizen science project called Radio Galaxy Zoo and described in a recent report in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society asks volunteers for help mapping the cosmos.

Well, how does it work?

The Radio Galaxy Zoo project enlists citizen scientists to pin down black holes and other objects that emit large amounts of energy through radio waves.

An online tutorial teaches the volunteers to compare radio and infrared views of the same patch of sky and match the radio sources they see with their host galaxies.

Researchers at the University of Western Australia say that, once completing this tutorial, the trained volunteers are as accurate as proper astronomers when it comes to finding jets coughed by black holes.

“Through the project, volunteers are given telescope images taken in both the radio and infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum and are asked to compare the pictures and match the ‘radio source’ to the galaxy it lives in.”

“Trained volunteers are as good as professional astronomers at finding jets shooting from massive black holes and matching them to their host galaxies,” they say.

Seeing how light cannot escape them, black holes cannot be observed directly. Rather, all researchers have to go on observing the jets of material they spew out in radio wavelengths.

To get the full picture, however, scientists need to also map their home galaxies. Here is where the views in optical wavelengths the volunteers are asked to compare with the radio images come into play.

Most of the times, the radio wavelengths and the optical wavelengths overlap, and in these instances, computer programs can automatically match them.

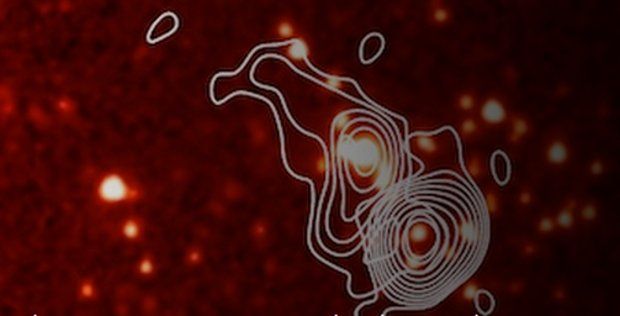

However, this isn't always the case. For instance, in the image below, the outlines show three blobs of radio emissions. These could account for either three galaxies arranged in a row or for one black hole and two jets.

By comparing the radio and the infrared images, citizen scientists can decide what the telescopes actually recorded. At least for now, computer programs are not quite as gifted at recognizing such patterns.

“If the infrared shows three galaxies in a row, lining up with the respective radio spots, then it’s probably three separate galaxies. If the only infrared source is in the center, then it’s probably a black hole and two jets,” scientists explain.

The project has made great progress

Researchers at the University of Western Australia say that, over just one year, citizen scientists working on the Radio Galaxy Zoo project helped match 60,000 radio sources to their host galaxies.

To get the job done, an astronomer working alone would have had to stick to this task for roughly 40 hours a week over about 50 years. Apparently, it pays to have more than just one pair of eyes stare at the sky.

It is expected that future all-sky radio surveys will deliver some 70 million sources of which 10% will be too weird and complex to be classified using computer algorithms. Making sense of them will fall to volunteers.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //