Scientists at the Rice University believe they may have finally found the answer to a decades-old riddle. Geologists found that Earth's mantle still features a host of light chemical elements inside, which shouldn't have endured there. In the early days of the planet, as volcanoes spewed out gases and produced the atmosphere, the mantle released most of its light elements into the newly-formed layer protecting our planet, but for some reason held on to some of the chemicals. The new Rice study looked at why this happened.

Among the most known of the elements still inside the mantle are helium and argon. Scientists have been puzzled as to how and why they endured in the devastating conditions of our planet's interior, given the fact that the natural tendency these substances exhibit is to escape through volcanoes, and into the atmosphere. Further adding to the mystery is the fact that the upper mantle appears to have none of these chemicals left, which means that whatever remains is concentrated in the lower mantle, even deeper than first thought. One of the explanations proposed for this mystery was the fact that the lower mantle has remained relatively isolated from the upper one, and thus managed to maintain a composition more closely-related to its initial state.

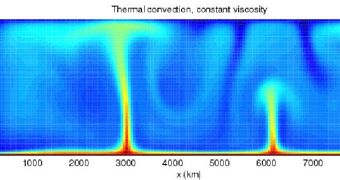

But the new investigation proposes the concept of “density traps,” phenomena going on inside the mantle that may have been responsible for the mystery. Working together, scientists at Rice, the University of Michigan, and the University of California in Berkeley (UCB), found that conditions existing in the mantle more than 3.5 billion years ago may have led to the formation of these special regions, some 400 kilometers below Earth's surface. The experts further explain that, inside these traps, special combinations of heat and pressure may have made liquids denser than solids.

This is very different from the way the mantle works today. Liquids that form within immediately rise to the surface, and exit the crust through volcanoes. But if the team is correct, then the unique conditions of the past allowed for liquids to stall, crystallize, and then sink even lower in the mantle, rather than rising. “When something melts, we expect the gas to get out, and for that reason people have suggested that the trapped elements must be in a primordial reservoir that has never melted,” says Rice associate professor of Earth science Cin-Ty Lee.

“That idea's become problematic in recent decades, because there's evidence that suggests all the mantle should have melted at least once. What we are suggesting is a mechanism where things could have melted but where the gas does not escape because the melted material never rises to the surface,” he concludes. The expert is also the lead author of a new paper detailing the investigation, which appears in this week's issue of the esteemed journal Nature. The work was sponsored by the Packard Foundation, and the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //