An international collaboration of scientists, led by investigators at VU University Amsterdam, say that the Moon has no volcanoes because its mantle – the layer of liquefied rocks underneath the crust – is extremely dense, and cannot rise towards the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes mostly form where tectonic plates meet. They are basically vents through which molten rocks from within our planet's mantle get pushed to the surface by extreme pressure levels.

However, the material does have some properties of its own that allow it to be pushed upwards. For starters, though it is dense, it's not overwhelmingly so. This means that it can fill magma chambers underneath volcanoes, and then literally flow on Earth's surface.

Apparently, the Moon has a layer of liquid magma under its crust as well, but the molten rocks contained within are simply too thick and dense to allow active volcanoes to develop. Researchers compare rising magma to a bubble traveling through water.

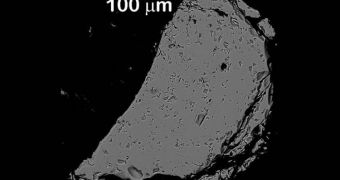

On Earth, the bubble can easily rise to the surface (i.e. through the crust), whereas within the Moon, the bubble is too heavy to do so. This conclusion belongs to a study conducted in the lab, on microscopic copies of Moon rocks.

The actual samples brought back by the Apollo mission were used as a starting point for creating the artificial replicas. The newly-obtained materials were then subjected to the temperatures and pressures researchers know acts on the lunar mantle.

By shining powerful X-rays through the mixture, the group was then able to measure the density of the resulting magma. Full details of the study were published in the February 19 issue of the top journal Nature Geosciences, SpaceRef reports.

Experts from the University of Paris 6/CNRS, University of Lyon 1/CNRS, the University of Edinburgh, and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), in Grenoble, France, were also a part of the research effort.

The X-ray measurements were compiled at the ESRF, which is an installation that is extremely qualified for such studies. The results obtained at the facility were then augmented with computer simulations of the same process, and were in tune with each other.

“Today, the Moon is still cooling down, as are the melts in its interior. In the distant future, the cooler and therefore solidifying melt will change in composition, likely making it less dense than its surroundings,” researcher Wim van Westrenen explains.

“This lighter magma could make its way again up to the surface forming an active volcano on the Moon – what a sight that would be! – but for the time being, this is just a hypothesis to stimulate more experiments,” adds the expert, who is based at VU University Amsterdam.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //