One of the longest-standing mysteries in medical sciences has been determining why is it that certain areas of the human brain develop so slowly after birth. A team of experts now seeks to tease out the answer by comparing our developing brains with those of monkeys.

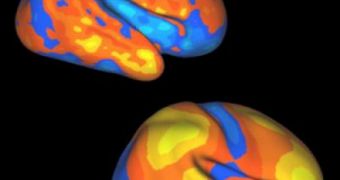

Regions of the brain that are responsible for underlying traits that make us human, such as advanced mental functions, language and reasoning, are the ones that develop the slowest. Experts believes this happens so that they can be influenced by early-life experiences, and consolidate accordingly.

The human body may very well allow these regions to grow as fast as muscles and bones do, but then it would deprive them of the chance to learn so much, and become interconnected in a way that is singular to each individual human.

A new study, from experts at the Washington University in St. Louis, shows that the cortical areas that change the most, and take the longest to do so, are the ones that underlie the differences between us and primates, our closest relatives.

“Through comparisons between humans and macaque monkeys, my lab previously showed that many of these high-growth regions are expanded in humans as a result of recent evolutionary changes that made the human brain much larger than that of any other primate,” David Van Essen, PhD, says.

“The correlation isn't perfect, but it's much too good to put down to chance,” adds the expert, who is the Edison Professor and head of the Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology.

“Pre-term births have been rising in recent years, and now 12 percent of all babies in the United States are born prematurely,” explains WUSM professor of pediatrics Terrie Inder, MD, PhD.

“Until now, though, we were very limited in our ability to study how premature birth affects brain development because we had so little data on what normal brain development looks like,” she says.

The expert and her team now plan to study how the human brain adapts itself to development limitations imposed by early birth. As soon as the group identifies these mechanisms, it could begin to develop ways of using them practically.

For example, they might be able to develop clinical strategies that would promote these adaptations to neural development limitations. The final result would be the normalization of cortical development, even in infants who are born prematurely, Daily Galaxy reports.

“This study and the data that we're gathering now could provide us with very powerful tools for understanding what goes wrong structurally in a wide range of childhood disorders, from the aftereffects of premature birth to conditions like autism, attention-deficit disorder or reading disabilities,” Inder concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //