Studies conducted over the past few years have demonstrated that rabbits are immune to prion diseases, Experts now believe they know why the animals cannot be harmed by the conditions, and that they will soon be able to synthesize new cures for humans, based on the new data.

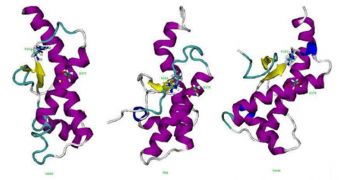

Prions are infections agents that are composed of proteins that are incorrectly folded. The way a protein folds is absolutely essential to determining its function. There are many such molecules that resemble each other, and only differ through the way they are folded. Their functions are entirely different.

Unlike conventional infectious diseases – which require that a microorganism bring DNA, RNA or both into the body – prion diseases can be caused by the body's own proteins. Mostly, they attack the brain and other neural tissue, and are untreatable and fatal.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker (GSS) syndrome, Fatal familial insomnia (FFI) and Kuru are the main prion diseases affecting humans. These conditions are degenerative, with death occurring several months to several years after infection.

In addition to rabbits, horses and dogs are immune to the condition too. Molecular biologists have spent the past few years trying to determine why this happens. Expert Jiapu Zhang, from the University of Ballarat in Australia, believes he may have uncovered an explanation.

He focused his research on determining how pH and temperature variations influence the proteins into changing their shape. In the immune animals, two parts of the immune proteins are bound by a salt bridge, which prevents the molecules from folding into an infectious form.

“This salt bridge might be a potential drug target for prion diseases,” Zhang says. What this means is that experts will have to find a way of triggering the creation of such salt bridges in human proteins too.

The same approach could be used in cattle and sheep as well. Mad cow's disease is a prion disease as well, so livestock losses could be minimized in the process as well. Zhang admits that his studies are just in their earliest stages.

However, the approach is very promising, the expert says, and definitely worth pursuing. Eliminating prion diseases would be a major step forward, considering their brutal and unforgiving nature, Technology Review reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //