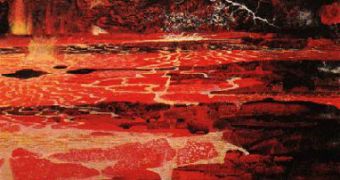

When you think about the way the planet chooses to drive its continents apart from one another, you're surely thinking thundering sound, catastrophic imagery and, generally, a lot of turmoil. Perhaps even scientists thought the same. This is why the recent event, which literally tears the African continent apart almost went unnoticed, only accompanied by small-scale earthquakes, albeit a large amount of them. But more thorough research indicated that dyke intrusions, the phenomena responsible for the event, are more quiet than expected.

A "dyking event" was recorded for the first time, although similar ones are thought to have happened in the recent decades. Its aftermath caused the emergence of a 10 km (6 miles) long and 1.5 meter (5 feet) wide magma wall wedging two tectonic plates meeting in the Tanzanian region. "Such dyking events had been included in theories, but researchers had never before been in the right place at the right time with the right equipment to record them," shared Eric Calais, professor of geophysics at Purdue University.

"The event was preceded by a slow slipping of the tectonic plates along a fault line. This also had not been seen before. Faults usually slip suddenly, which produces earthquakes, but this was a very seismically quiet course of events that lasted about one week," he explained, as cited by PhysOrg. "To break a continent apart, one needs to overcome the strength of the Earth's lithosphere," he continued.

"But when we calculate the forces available from plate tectonics, we find that they are not large enough to do the job. We know that continents break apart and have done so repeatedly in the geological past. So, how can it happen? One way is to add a little push to the system, and this is exactly what dyke intrusions do. Eventually, if these events occur over and over again for millions of years, an ocean will form between the two plates," Calais claimed.

The expert had heard repeated reports about moderate seismic activity in the region, but it was the sheer number of events (over 600) that caught his attention. Luckily, he had immediate access to GPS, seismic activity and InSAR data that put together the pieces of the puzzle; otherwise, the event would have passed unnoticed. "The displacement was much too large given the small size of the earthquakes, which was the first lead that something unusual was happening," he explained.

"Soon after these earthquakes, one of the volcanoes in the area entered an explosive eruptive stage, which indicated that magma was involved. So we had an idea this might be a dyking event." Such events are expected to occur in the near future, indicates the scientist.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //