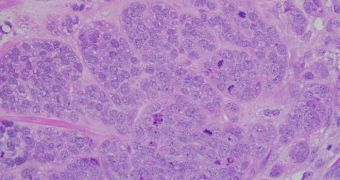

A group of investigators from the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel recently conducted a new study that revealed why breast cancer tends to become resistant to certain forms of hormone therapy. The work may pave the way towards new types of treatments that may improve overall survivability and cancer statistics.

This particular study focused on a hormone therapy that uses chemicals such as tamoxifen. In patients treated thusly, tumor resistance to medication often occurs, and scientists haven't been able to figure out why this happened until now.

The scientists were able to determine that a receptor located on the surface of breast cancer tumor cells is responsible for this phenomenon. Apparently, the receptor can exhibit impromptu mutations, which no longer allow it to bind tamoxifen, and destroy the cancer cell.

Details of the investigation were published in the latest issue of Cancer Research, a scientific journal published by the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). The work was led by the head of the medical oncology department at the SMC, Ido Wolf, MD.

The work is very important because it has the potential to drastically improve survivability among breast cancer patients. At this point, if hormone therapy fails, sufferers have to undergo a highly-toxic regimen of chemotherapy, an approach that has numerous negative side-effects.

“Virtually all patients with metastatic breast cancer who initially respond to endocrine [hormone] treatments eventually develop resistance to these treatments,” Wolf explains.

“We identified a new mutation in the estrogen receptor, which is the target for endocrine treatments, and the mutation makes the receptor more active and resistant to endocrine treatments. Importantly, we identified the mutation in 38 percent of our patients,” the team leader adds.

The finding was made possible through the use of high-tech, high-throughput sequencing technologies. The mechanism through which the cancer cells shield themselves is very simple, but researchers had no way of determining precisely which mutation was responsible for the effect.

But Wolf says that luck played a role in this research as well. “Previous studies mostly looked at either the primary tumor or metastases before treatment, which may be why this mutation was never detected. We were able to detect it because we sampled tumors at the right time,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //