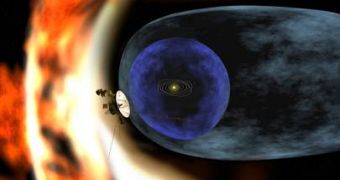

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are two of the most important spacecrafts in the history of space and solar system exploration, and currently the only two man-made objects to go beyond the limits of the solar system. Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock, the area of space where solar wind and interstellar radiation collide, towards the end of 2004, followed closely by Voyager 2 which exited the solar system in August last year.

In fact, according to the predictions made using the data received from Voyager 1, Voyager 2 should have crossed the termination shock much later. Voyager 1 reached the northern edge of the heliosphere at a distance of 12.48 billion kilometers away from the Sun, while Voyager 2 crossed the termination shock at only 11.2 billion kilometers from the Sun through the southern region, suggesting that the shape of the heliosphere is asymmetrical and squashed in the southern region.

"The solar wind is blowing outward trying to inflate this bubble, and the pressure from interstellar wind is coming in," said Edward Stone, physicist and Voyager project scientist at Caltech, who recently published the detailed findings of the two spacecrafts.

Researchers believe that the reason for this asymmetrical shape is that in the southern region of the heliosphere the interstellar magnetic field is somehow much stronger, thus applying more pressure in order to bend the heliosphere slightly inwards. According to calculations, the shape of the heliosphere can vary significantly over a period of 100,000 years or so as a result of magnetic field turbulences.

"We're actually seeing the shock for the first time," said John Richardson, principal scientist for Voyager's Plasma Physics instrument at MIT, pointing out the fact that at the time when Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock, its plasma detector wasn't operational since it had failed soon after passing Saturn. The instrument of Voyager 2 however was working just fine at the time of the crossing, allowing researchers to get an unprecedented view of the conditions on the edge of the heliosphere.

Radiation coming from the Sun rushes towards the outer regions of the solar system at supersonic speeds, and reaches temperatures as high as 10,000 Kelvin. At the same time, interstellar radiation travels towards the Sun and collides with the solar wind at the terminal shock, during which time the temperature should reach 1 million Kelvin. Voyager 2 on the other hand showed that the temperature only reaches 100,000 Kelvin.

According to Richardson, the missing energy can be accounted for through the fact that neutral atoms enter the heliosphere as well and take away as much as 80 percent of the energy released in the terminal shock as they become energized. One of the currently unsolved problems regarding the processes that take place in the outer limits of the solar system, is that scientists cannot yet explain why the solar wind slows down just before encountering the terminal shock.

"Somehow the solar wind knows the shock is coming before it gets there, and theory says that shouldn't be," Richardson said. From a speed of 396.8 kilometers per second, the velocity of the solar wind drops to 297.6 kilometers per second just before the terminal shock, after which it slows down to only 150 kilometers per second.

"My guess is five to seven years to reach interstellar space. There's a very good chance that Voyager I will send the first data back from there," said Stone regarding the possibility that future observations with the two spacecrafts will clarify the currently unsolved mysteries.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //