A team of researchers at the University of Calgary found what they called 'the smoking guns' of the latest Permian extinction – a mix of massive volcanic eruptions, burning coal and greenhouse gas.

During the latest Permian extinction, some 250 million years ago, 96% of life was erased from the seas, and 70% from land.

University of Calgary researchers think they have found evidence of what happened at that time – huge volcanic eruptions burnt very high volumes of coal, causing ash clouds that had a massive impact on the oceans.

Dr. Steve Grasby, adjunct professor in the University of Calgary's Department of Geoscience and research scientist at Natural Resources Canada, says that “this could literally be the smoking gun that explains the latest Permian extinction.”

Grasby and his colleagues discovered layers of coal ash in rocks from the extinction boundary in Canada's High Arctic, which represent the first direct proof to support this theory.

The Permian-Triassic extinction is very different from the extinction of the dinosaurs, 65 million years ago, because the causes of this huge event were unknown.

The researchers explain that at the time of the extinction, there was a single super continent on Earth, called Pangaea, and life went from deserts to profuse forests.

As for animals, it seems that four-limbed vertebrates widened their diversity, having among them primitive amphibians, early reptiles and synapsids – the group that includes mammals.

The devastating volcanoes, called the Siberian Traps, are now found in northern Russia, around the Siberian cities of Tura, Yakutsk, Noril'sk and Irkutsk.

This area measures just under two-million-square kilometers, which makes it greater than that of Europe, and the reason coal-ash layers were found in Canada's arctic is because the ash plumes from the Siberian volcanoes traveled here.

Prior research suggested that the volcanic eruptions through the Siberian coal beds, caused significant greenhouse gases that accelerated global warming.

Grasby says that this “research is the first to show direct evidence that massive volcanic eruptions – the largest the world has ever witnessed –caused massive coal combustion thus supporting models for significant generation of greenhouse gases at this time.”

Along with Dr. Benoit Beauchamp, a professor in the Department of Geoscience at the University of Calgary, they studied the formations of the coal-ash layers.

To obtain maximum information on the strange organic layers they had discovered, the two asked the professional opinion of Dr. Hamed Sanei, adjunct professor at the University of Calgary and a researcher at NRCan.

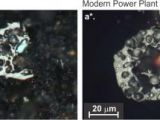

Beauchamp explained they “saw layers with abundant organic matter and Hamed immediately determined that they were layers of coal-ash, exactly like that produced by modern coal burning power plants.”

“Our discovery provides the first direct confirmation for coal ash during this extinction as it may not have been recognized before,” adds Sanei.

Even though Earth was already heating up before the volcanic eruptions, the ash could have sped up the destruction process, by decreasing the levels of oxygen and suffocating the oceans.

“It was a really bad time on Earth,” added Grasby.

“In addition to these volcanoes causing fires through coal, the ash it spewed was highly toxic and was released in the land and water, potentially contributing to the worst extinction event in earth history.”

These findings are published in Nature Geoscience.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //