Though researchers don't have unlimited amounts of knowledge on black holes, they are not completely in the dark either. As such, they were able to figure out that two nearby black holes, of the variety that exists at the center of massive galaxies, were not behaving as they were supposed to. The group behind the study says that one of the supermassive behemoths is several times as bright as it should normally be, whereas the other is located at an entirely different position in space than calculations led astronomers to believe. The two black holes are not located in the same galaxy.

Understanding the evolution of galaxies, and how black holes emerged and developed, are not areas of research that can be made sense of independent of each other. Astronomers have come to believe that these types of structures form an integrated whole, and that they need to be studied together. Therefore, the two new studies that were presented in Miami, at the 216th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS 2010), should provide additional insight for experts to use in their analyses. The authors of the two papers said that some of the results contained within were surprising, to say the least.

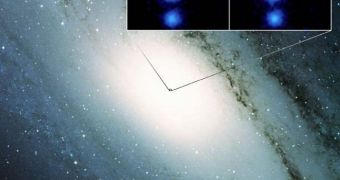

In the first paper, experts dealt with the strange phenomena that have been taking place in our closest neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy. Astronomers noticed about 4 years ago that the supermassive black hole that lied at the core of the formation became no less than 100 times brighter than before, following an outburst. The phenomena took place on January 6, 2006, Space reports. “We have some ideas about what's happening right around the black hole in Andromeda, but the truth is we still don't really know the details,” explains Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) expert and study team member Christine Jones.

“It's important to figure out what's going on here because the accretion of matter onto these black holes is one of the most fundamental processes governing the evolution of galaxies,” added Zhiyuan Li, who is also an expert at the CfA. “The black holes in both Andromeda and the Milky Way are incredibly feeble. These two 'anti-quasars' provide special laboratories for us to study some of the dimmest type of accretion even seen onto a supermassive black hole,” he adds.

In the second paper, scientists looked at the central regions of M87, a relatively-nearby galaxy, located within the northern Virgo Cluster, some 55 million light-years away. Using data from the Hubble Space Telescope, a team of investigators was able to determine that the supermassive black hole they expected to find at the core was actually not in the center of the galaxy. The reason for this displacement has largely been attributed to past merger events, in which two SMBH (smaller supermassive black holes) joined forces, causing the resulting structure to be located off-set from its normal position.

“The theoretical prediction is that when two black holes merge, the newly combined black hole receives a 'kick' due to the emission of gravitational waves, which can displace it from the center of the galaxy. We also find, however, that the iconic M87 jet may have pushed the SMBH away from the galaxy center,” explained Florida Institute of Technology expert Daniel Batcheldor, who was the lead researcher on the new investigation.

“What may well be the most interesting thing about this work is the possibility that what we found is a signpost of a black hole merger, which is of interest to people looking for gravitational waves and for people modeling these systems as a demonstration that black holes really do merge,” concluded Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) expert and study member Andrew Robinson.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //