According to a new report by experts from the Connecticut Children's Medical Center, in Hartford, Connecticut, severe-trauma patients who receive blood transfusions containing red blood cells older than one month have a twice as large chance of dying than similar patients who receive fresh blood. In keeping consistent with previous reports on cardiac-surgery patients, the researchers followed the risk up to months after the original transfusion took place, e! Science News reports.

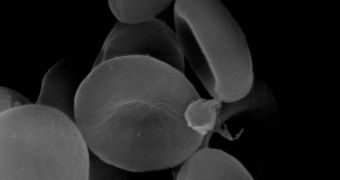

In charge of the investigation were CCMC pediatric intensivists Philip Spinella and Christopher Carroll, who published their work in the latest issue of BioMed Central's open-access scientific journal Critical Care. Their research followed up 202 severe-trauma patients from the Hartford Hospital, who had received five or more units of red blood cells during the course of their treatment. Their results were fairly straightforward. Even one unit of old, red blood cells doubled the risk of people developing deep vein thrombosis, or dying on account of multiple-organ failure.

The researchers separated the patients into two groups, and each of the groups received the same amount of RBC blood. This was done in order to eliminate criticism that had been received by other, similar studies. Critics argued that it was the amount of transfused blood that was the main factor at work, and not the age of the blood units themselves. The new study is one of the few to date that document a strong link between old-blood transfusions and death, and should therefore be taken into account by physicians working on trauma patients from now on.

According to official US statistics, more than 29 million units of blood were given to patients around the country in 2004, as this is the procedure normally associated with treating intense, life-threatening trauma. Spinella and Carroll argue that, at least for the critically injured patients, old, red blood cells should be avoided at all costs. Fresh units should thus be made readily available in operating rooms, they argue, if all the patients are to have an equal chance of survival.

“The preferential use of younger RBCs to critically ill patients has the potential to increase waste due to outdating. Since blood is often a scarce resource this is important and methods need to be developed to minimize waste while providing the most efficacious and safe blood product for a given patient,” Spinella says. “These important findings should encourage research into the effects of old blood and coagulation in critically ill patients. With the widespread of use of red blood cell transfusion for critically injured patients, this study has the potential to cut deaths in hospitals around the world,” the experts conclude.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //