Experts managing the NASA/ESA Cassini spacecraft have recently announced that the interior of Saturn's largest moon Titan is most likely made up of rock and large amounts of ice. They base their conclusions on in-orbit analysis of Cassini's trajectory, as it swooped past the natural satellite during several flybys. Planetary scientists know that the composition of a space rock's interior determines the type of gravitational pull it will exert on nearby objects, and so they looked at how much the trajectory the space probe took modified from the planned route. They were thus able to map the interior of Titan in great detail, scientists at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California, say.

“These results are fundamental to understanding the history of moons of the outer solar system. We can now better understand Titan's place among the range of icy satellites in our solar system,” explains Bob Pappalardo, who is a Cassini project scientist, and also a part of the JPL team that managed the spacecraft. According to the new data, it would appear that Titan has evolved rather differently from all planets in the inner solar system, such as Earth and Mars. It is also different from objects in the same class, such as icy moon Ganymede, which revolves around Jupiter. This particular natural satellite has a core that has clearly differentiated into layers, whereas Titan's did not.

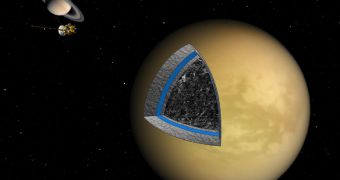

According to the new maps, the interior of the moon is laden with ice, which is mixed thoroughly with rock. There is no clear differentiation or layers of the two materials. This happened most likely because the interior of Titan never got sufficiently warm to allow for that to happen. However, it was also found that the topmost 300 miles (500 kilometers) of its surface are made entirely of ice, with no rock inside. The material begins to appear at great depths, in various concentrations, geologists believe.

“To avoid separating the ice and the rock, you must avoid heating the ice too much. This means that Titan was built rather slowly for a moon, in perhaps around a million years or so, back soon after the formation of the solar system,” says California Institute of Technology (Caltech) professor of planetary science David J. Stevenson, one of the coauthors for the new paper.

“The ripples of Titan's gravity gently push and pull Cassini along its orbit as it passes by the moon and all these changes were accurately recorded by the ground antennas of the Deep Space Network within 5 thousandths of a millimeter per second [0.2 thousandths of an inch per second] even as the spacecraft was over a billion kilometers [more than 600 million miles] away. It was a tricky experiment,” concludes Sapienza University professor and Cassini radio science team member, Luciano Iess. He is also the lead author of the new paper detailing the findings.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //