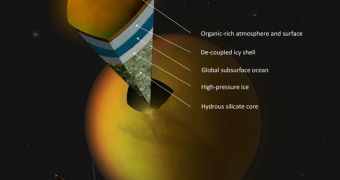

According to a careful analysis of data sent back to Earth by the NASA Cassini spacecraft, the largest Saturnine moon, Titan, may have an ocean of liquid water lurking under its surface. Interestingly, the moon is most renowned for its liquid hydrocarbon-based atmospheric cycles.

Details of the new investigation appear in the June 28 issue of the top journal Science. The most important conclusion featured in the work is that the moon's interior is not made up exclusively from solid materials. Previously, it was thought that rocks were the main constituents inside Titan.

It's important to note here that the moon is completing a single orbit around Saturn in about 16 days. The object is very close to its host, too, so the tides it develops are very high. It's very likely that its surface displays ever-changing tidal deformities.

Cassini measured the amount of squeezing and stretching that Saturn causes on Titan, and determined that the moon should exhibit solid tides around 1 meter (3 feet) high. However, data from the spacecraft indicate that the height of solid tides reaches 10 meters (30 feet).

This suggests that the object's interior is not made up exclusively of solid material. “Cassini's detection of large tides on Titan leads to the almost inescapable conclusion that there is a hidden ocean at depth," expert Luciano Iess says.

“The search for water is an important goal in solar system exploration, and now we've spotted another place where it is abundant,” adds the scientist, the lead author of the Science paper, and a member of the Cassini science team. He is based at the Sapienza University, in Rome, Italy.

In order to conduct this study, scientists used Cassini data collected during six flybys, which took place between February 27, 2006 and February 18, 2011. The research team was especially interested in the deformities caused on the moon's surface at several key points in its orbit around Saturn.

“We were making ultrasensitive measurements, and thankfully Cassini and the DSN were able to maintain a very stable link,” Cassini science team member Sami Asmar explains, who is based at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, California.

“The tides on Titan pulled up by Saturn aren't huge compared to the pull the biggest planet, Jupiter, has on some of its moons. But, short of being able to drill on Titan's surface, the gravity measurements provide the best data we have of Titan's internal structure,” the expert concludes.

If this study is correct, then scientists may have just discovered one of the mechanisms the Saturnine moon uses to create methane, as well as one of the locations where the chemical is stored on Titan.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //