The presence of tube-like structures made up of plasma high over our heads, in Earth's magnetosphere, was first proposed by scientists decades ago.

Still, it was only recently that, with the help of the Murchison Widefield Array radio telescope, a team of researchers at the University of Sydney in Australia managed to put together a three-dimensional view of these plasma tubes.

In doing so, the specialists produced visual evidence that the plasma structures present in our planet's magnetosphere that were first described by the scientific community well over 60 years ago really do exist and aren't just a theory.

Explaining the formation of these plasma structures

The University of Sydney team behind this investigation details their findings in a paper published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. In this report, they explain that, just like a bar magnet, Earth has a magnetic field around it.

This magnetic field forms a bubble of sorts around our planet that researchers call the magnetosphere. In turn, the magnetosphere comprises the ionosphere, which is its innermost layer and goes up to about 1,000 kilometers (620 miles), and the plasmasphere.

With the help of the Murchison Widefield Array telescope, scientists found that both the ionosphere and the plasmasphere are crisscrossed by tube-like structures of plasma created when particles in the atmosphere are ionized by radiation from the Sun.

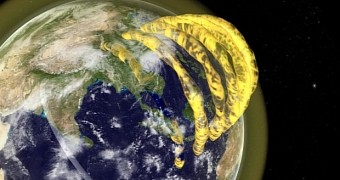

The plasma tubes begin high up in the ionosphere and extend well into the plasmasphere, as illustrated in the image accompanying this article. They do not stand alone, but are instead accompanied by other more oddly shaped plasma structures.

“We measured their position to be about 600 kilometers [approximately 370 miles] above the ground, in the upper ionosphere, and they appear to be continuing upwards into the plasmasphere,” study leader Cleo Loi explained in an interview.

What do we care about what Earth's magnetosphere looks like?

The trouble with plasma present in our planet's magnetosphere is that it can interfere with signals traveling through it, researcher Cleo Loi explains in a video released together with the Geophysical Research Letters report and which you can find below.

For instance, it can mess with both civilian and military satellite-based navigation systems. Hence, the more scientists know about plasma structures in Earth's atmosphere, the better they can predict and prevent the signal distortions they stand to cause.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //