A group of investigators from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge, says that ongoing clinical trials are providing them with hope that a new approach to treating cancer may in fact be very effective.

The technique, which relies on the use on targeted, therapeutic nanoparticles, allows the tiny structures to bypass healthy cells, and only accumulate within tumor cells. This works for a multitude of cancer types, regardless of where they are in the body.

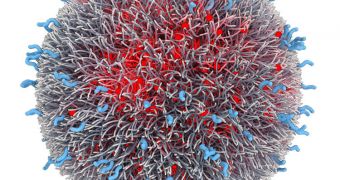

Researchers in the team say that the secret “ingredient” is a homing molecule that is outfitted to the exterior of the nanoparticles. This addition enables the nanoparticle to bind exclusively to cancer cells.

According to the team, these are the first synthetic nanoparticles to be approved for human clinical trials. The structures were originally developed by a collaboration of scientists at MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston.

Inside the particles, experts introduce docetaxel, which is a drug used in standard chemotherapy. Primarily, oncologists employ it to address lung, prostate and breast cancers, but not exclusively.

What researchers showed in the new research is that the nanoparticles they developed are able to target a receptor located on the outside of tumor cells with extreme accuracy, bypassing healthy cells and tissues it comes in contact with before reaching its destination.

This is very important, since the poor cancer-targeting skills of conventional drugs is what makes chemotherapy trigger so many adverse side-effects. This treatment method is also very toxic to healthy cells, killing everything it comes across indiscriminately.

In a new paper describing the findings, published in the April 4 issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine, the team shows how this problem is bypassed through the use of nanoparticles.

The main advantages this delivery system entails are a high degree of precision in targeting cancer cells specifically, as well as the fact that it protects the drugs it carries from the actions of the immune system. This enables doctors to prescribe smaller doses of the drugs they generally use.

“The initial clinical results of tumor regression even at low doses of the drug validates our preclinical findings that actively targeted nanoparticles preferentially accumulate in tumors,” Robert Langer says.

“Previous attempts to develop targeted nanoparticles have not successfully translated into human clinical studies because of the inherent difficulty of designing and scaling up a particle capable of targeting tumors, evading the immune system and releasing drugs in a controlled way,” he adds.

Langer is the David H. Koch Institute Professor at the MIT Department of Chemical Engineering, and was also the senior author of the new paper.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //