According to data sent back by the Venus Express spacecraft, it would appear that the poisonous atmosphere surrounding our neighboring planet is actually a lot thinner than initially calculated.

The datasets that led to these conclusions were not collected from an orbital perch, but rather from a series of low-altitude flybys that the space probe did through the planet's atmosphere.

The flights took place in July and August 2008, October 2009, and February and April 2010. Experts say that the main point of the flybys was to determine the density of the upper atmosphere above the polar regions of Venus.

This is the first time that such an elaborate and complex experiment is attempted on the planet, explains officials from the European Space Agency (ESA), who manage Venus Express.

“It would be dangerous to send the spacecraft deep into the atmosphere before we understand the density,” says Pascal Rosenblatt of the possibility of sending a manned mission to the planet.

He is a member of the team that conducted the new investigation, and he holds an appointment at the Royal Observatory of Belgium. Space exploration missions cannot be devised without knowing the atmospheric density of the target object.

The expert goes on to say that Venus Express has thus far beamed back 10 sets of measurements, which all show that the planet's atmosphere is nearly 60 percent thinner than experts calculated.

An international group of scientists is currently investigating whether a previously undetected natural phenomenon is at work in underlying these readings.

The team is being led by scientist Ingo Mueller-Wodarg, who is based at the Imperial College London (ICL), in the United Kingdom.

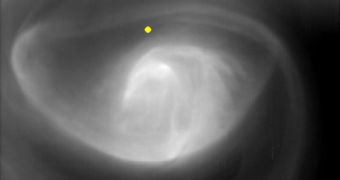

One interesting conclusion that the space probe hints at is that there are large density variations between the night and day side of the planet. This was evidenced in a series of torque experiments.

As the spacecraft was flying some 175 kilometers above the surface, one of its solar panels was turned edge-on, which allowed the atmosphere to twist and turn the probe.

At this point, Venus Express needs to compensate for orbital glitches every 40 to 50 days, by firing its engines. But fuel is in short supply, and it will run out by 2015.

A scenario in which its orbit can be lowered using the drag of Venus’ atmosphere to slow down the spacecraft is possible, but doing so requires delicacy and time.

“The timetable is still open because a number of studies have yet to be completed,” explains expert Håkan Svedhem, an Project Scientist for Venus Express at ESA.

“If our experiments show we can carry out these maneuvers safely, then we may be able to lower the orbit in early 2012,” he says.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //