Many experts currently consider that Mars' reddish hue is owed to rusted rocks, which were subjected to the action of the water that once covered the planet. This idea has been proposed and debated for a long time, but recent laboratory studies are beginning to infirm it, some experts say. The investigations have revealed that the color is actually generated by large-scale grinding processes of the rocks, and that water need not be inserted into the equation. The new idea has been presented at the European Planetary Science Congress, in Potsdam, Germany, by Dr. Jonathan Merrison, AlphaGalileo reports.

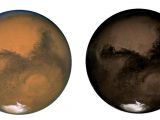

“Mars should really look blackish, between its white polar caps, because most of the rocks at mid-latitudes are basalt. For decades we assumed that the reddish regions on Mars are related to the water-rich early history of the planet and that, at least in some areas, water-bearing heavily oxidized iron minerals are present,” Dr. Merrison, who is an expert at the Aarhus Mars Simulation Laboratory (MSL), in Denmark, said before the conference.

Experts at the research institution have devised a series of experiments to prove that water played an inconsequential part in shaping the planet's colors. They essentially devised a new method of simulating the sand transport on Mars, by constructing hermetically sealed glass flasks, in which quartz (sand) samples were made to tumble and roll over for several months. Each of the flasks was turned over ten million times during the study.

Some ten percent of the sand was reduced to dust within seven months, the team noticed. In the containers in which the scientists added powdered magnetite, the sand turned to red dust even faster. The magnetite is an iron oxide that can be found plentifully in Martian basalt, the predominant type of rock on the Red Planet.

“Reddish-orange material deposits, which resemble mineral mantles known as desert varnish, started appearing on the tumbled flasks. Subsequent analysis of the flask material and dust has shown that the magnetite was transformed into the red mineral hematite, through a completely mechanical process without the presence of water at any stage of this process,” the expert added.

“By simulating the conditions and developing accurate analogues of the Martian environment, we will certainly gain a deeper understanding of its dusty nature. In particular, developing better analogues of the Martian surface and atmosphere is vital in interpreting observations made on Mars by landers as well as pioneering the next generation of experiments to be flown,” Merrison concluded.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //