According to a new scientific study, conducted by researchers at the University of Utah, and published in the August 6th issue of the respected scientific journal Nature, the new and young New Zealand tectonic plate is slowly reaching maturity, benefiting from an unexpected source of help – water deposits located deep underground. The entire subduction zone, where the Pacific Plate moves underneath the Australian Plate, is constantly “irrigated,” which allows it to mature faster, and to start harboring the potential for extremely powerful earthquakes, similar to those on the American west coast, the team reveals.

The “young” subduction zone, called Hikurangi, is termed as such because it was only in the last 20 million years that the Pacific plate began touching the Australian one, and submerging under it. These processes take place at an extremely slow rate, and 20 million years is a very short time in geological terms. The threat of volcanism, earthquakes and tsunamis comes from the fact that the Pacific Plate moves under its opponent at a 45-degree inclination, which means that “strike-slip” pressures occur, similar to those in the San Andreas fault line.

As the large plates continue their unstoppable threat on the ocean of magma that is our planet's mantle, there is nothing to prevent them from colliding. If two plates are jammed against each other, they will stay still for a while, as energy and pressure builds up behind them. Eventually, the pieces of rock holding them back will snap out of place, and the plates will vigorously rearrange themselves in a new pattern, with all tension between them eliminated. This phenomenon is what people call earthquakes.

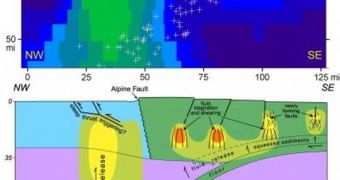

Using a scientific investigation method known as magnetotelluric sounding, which is similar to CAT scans, in that it makes use of electromagnetic radiation resonance to assess magma density, the research team took measurements of what's underneath the Hikurangi subduction zone at 67 sites along a 125-mile line passing through New Zealand. Their most amazing discoveries were:

1. Beneath the South Island's eastern coast, where the Pacific Plate begins to dive under the Australian Plate, water is released about 10 miles underground. It comes from seafloor sediments that are squeezed as they are carried underground on the subducting Pacific Plate. Much of the water rises upward into the overlying crust of the Australian Plate, cracking the crustal rock further to create and widen existing cracks.

2. Farther west, water is released from hydrated rock – rock with chemically bound water – within the subducting Pacific Plate. The water collects within cracks roughly 6 to 20 miles underground in the “ductile,” or taffy-like, part of the Earth's crust.

3. The largest accumulation of water beneath the subduction zone is also the deepest and farthest west beneath the South Island. Freed by the action of heat and pressure on hydrated minerals, the water forms a huge plume extending upward from depths of 60 miles or more. It appears these fluids trigger major earthquakes – and did so during magnitude-7 and larger earthquakes in the Murchison area in the early 20th century.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //