From cold to hot, sweet to bitter, there must be a gene that enables us to detect these sensations.

After years of research, scientists have finally detected the gene responsible for the cold sensation, at least in mammals. The gene, named TRPM8, could lead to the development of analgesic drugs provoking cold sensation or fighting against pain linked with cold sensation.

"This study represents the first demonstration that a single gene is responsible for most cool temperature sensation," said lead researcher Ardem Patapoutian, from the Department of Cell Biology at Scripps Research and the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation.

"Many previous candidates have been postulated to play a role in our ability to sense cool temperatures, but none have withstood the test of genetics".

Patapoutian's team discovered the role of this gene in controlling cold sensation by testing mice genetically modified to lack the TRPM8 gene.

Genetically engineered mice placed in a space where they could choose between 18?C and 31?C displayed no preference in the temperature, while normal mice dislike cold temperature and wittingly avoid cold areas in favor of warmer ones.

"It's pretty amazing that one gene could impact thermal sensation this much," said co-author Ajay Dhaka, a Scripps Research postdoctoral fellow.

"It really highlights the importance of the peripheral nervous system and how temperature affects our behavior".

The genetically modified mice were also little sensitive to the acetone, whose application on the skin provokes an unpleasant cold sensation: normal mice flick their paws and lick them when acetone is applied.

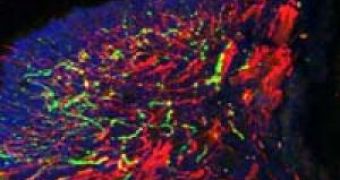

TRPM8 encodes for an ion channel protein encountered at the tips of sensory neurons located in the skin. It seems that the TRPM8 ion channel is turned on by low temperature provoking cold sensation.

"TRPM8 acts as a gate. At warm temperature it remains closed, but opens when exposed to cool temperature." said Dhaka.

Another aspect: The engineered mice did not lose their pain sensitivity when exposed to extreme cold, unlike normal mice which felt decreased pain sensation when exposed to -1? C cold plates. It is known that cold, even if painful by itself in some instances, can deaden pain: ice is often put on injury to relieve pain. The precise mechanisms through which the same sensation can be unpleasant or pleasant under various circumstances is not precisely known.

"It would be really interesting to find out how the brain takes essentially the same signal and, depending on context, interprets it differently," said Dhaka.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //