HIV is a deadly, incurable virus, that infects tens of millions of people, and no scientific modern approach has been effective so far, so a group of researchers at Yale University, US, led by Craig Crews, thought that an ancient method might do the trick.

Everyone knows the story of the Trojan horse, whether it is from books or from movies, but in order to apply it in medicine, the researchers had to develop a 'Trojan horse' molecule that uses HIV to trigger the release of a drug that destroys the virus.

Because of the way that HIV infects patients' bodies, Crews concluded that the best way to kill it is to kill every infected cell, within the body.

And even if this may sound a bit radical, and even scary, there's really nothing to worry about, since in chronic HIV infection the virus is stored in a small reservoir of cells.

Ali Tavassoli, a researcher of the University of Southampton, UK who investigates small molecules that inhibit diseases including HIV, thinks that Crews' idea was 'really interesting', and even if there is no evidence that the molecule can get into cells, he added that he would be 'very surprised if it was not cell permeable.'

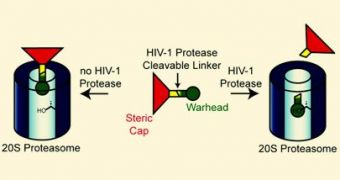

This molecule consists of a proteasome inhibitor bound to a steric cap that blocks the entrance of the inhibitor in the proteasome, unless HIV is present in the cell.

If the virus is present, one of its own enzymes will split the bulky cap, allowing the drug to eventually kill the infected cell before the virus can replicate and spread.

The scientists had already developed a drug – a cytotoxic epoxyketone proteasome inhibitor currently in Phase III clinical trials for the treatment of cancer, which they now took and modified, so that it would only be activated in HIV infected cells.

To do so, they added a branched dendrimer of lysine molecules, linked to the proteasome inhibitor by a protein sequence that is cleaved by the enzyme HIV-1 protease.

The group proved that even if normally the dendrimer cap would prevent the drug molecule from reaching its target in the proteasome, when HIV-1 protease is present, the cap is cleaved and the drug can react with its target.

Crews explained that most HIV is dormant, so it could not express enough protease to activate the drug, RSC reports.

On the other hand he added that “it may be counter intuitive, but for this strategy to work we would actually have to reactivate the latent virus.”

Tavassoli described this as being 'difficult,' although this is an area of active research.

According to Crews, “what prompted all of this was the Grand Challenges Explorations grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation.

“They wanted us to think big about curing AIDS.”

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //