California Institute of Technology (Caltech) researchers have recently been able to identify the exact portion of the human brain that is responsible for exercising self-control, as in, for instance, when you decide to skip a fat-laden meal and to eat something healthier. Although it may seem simple to refuse at first, actually turning such a meal down requires a high degree of self-control, even if exercised unconsciously, and especially for people who eat them regularly. The Caltech team has managed to identify the differences that occur between the brains of people who can easily restrain themselves and those of the individuals who find doing this next to impossible.

“A very basic question in economics, psychology, and even religion, is why some people can exercise self-control but others cannot. From the perspective of modern neuroscience, the question becomes, 'What is special about the circuitry of brains that can exercise good behavioral self-control?' This paper studies this question in the context of dieting decisions and provides an important insight,” Caltech Associate Professor of Economics Antonio Rangel, who has also been the principal investigator for the new scientific study, explains. Details of the find appear in the May 1st issue of the journal Science.

“After centuries of debate in social sciences, we are finally making big strides in understanding self-control from watching the brain resist temptation directly. This study, and many more to come, will eventually lead to much better theories about how self-control develops and how it works for different kinds of temptations,” Caltech Division of Humanities and Social Sciences Robert Kirby Professor of Behavioral Economics Colin Camerer, who has also been one of the study co-authors, adds.

During the study, the team analyzed the behavior of 37 volunteers, who were selected from a larger number of participants. Those who remained were divided into two groups, one made up of 19 people – who exercised an amazing self-control – and the second made up of 18 test subjects, who exhibited little to no self-control. Their brains were then observed using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

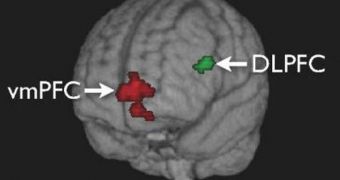

The results revealed that the levels of activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, or vmPFC, which had been previously associated with value-based decision-making, were very low in individuals who were able to exercise self-restraint. “In the case of good self-controllers, however, another area of the brain – called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [DLPFC] – becomes active, and modulates the basic value signals so that the self-controllers can also incorporate health considerations into their decisions,” Rangel says.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //