According to the results of a new scientific investigation by researchers at the University of Sheffield, in the United Kingdom, it would appear that Earth's climate and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations were regulated by a single biological mechanism over the past 24 million years.

The research team says that forests played a critical role in developing a stable global climate, and in controlling the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. When CO2 levels were too low, and threatened to stop plant growth, forests responded by slowing down their carbon intake.

Whenever there is too little CO2 in the atmosphere, our planet loses a significant part of its greenhouse effect, which contributes to keeping it warm. Global warming, for example, occurs when CO2 amounts are too high, and they exacerbate the greenhouse effect and its planet-wide implications.

Details of the new research appear in the latest issue of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) open-access journal Biogeosciences. The lead author of the paper was University of Sheffield professor Joe Quirk, Astrobiology Magazine reports.

“As CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere fall, the Earth loses its greenhouse effect, which can lead to glacial conditions. Over the last 24 million years, the geologic conditions were such that atmospheric CO2 could have fallen to very low levels – but it did not drop below a minimum concentration of about 180 to 200 parts per million. Why?” he says.

Before humans started releasing billions of tons of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, CO2 concentrations were kept in check via a natural mechanism. Events such as volcanic eruptions released vast amounts of aerosols, while forests and weathering continents stored carbon.

In the new paper, the team argues that decreased atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations (from 1,500 parts per million to 200 ppm) basically act as a carbon starvation break, reducing the rate at which forests break down minerals and nutrients in the ground by around 33 percent. This makes carbon uptake more difficult for trees.

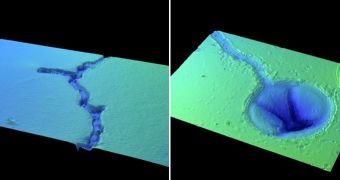

“We recreated past environmental conditions by growing trees at low, present-day and high levels of CO2 in controlled-environment growth chambers. We used high-resolution digital imaging techniques to map the surfaces of mineral grains and assess how they were broken down and weathered by the fungi associated with the roots of the trees,” Quirk concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //