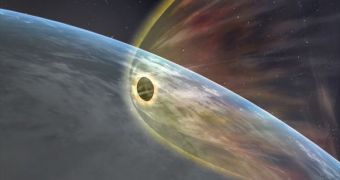

A few weeks ago, the skies over the Australian desert were lit up, as the Hayabusa space probe's sample canister blazed down to Earth. The device was ejected by a mothership that on June 13 concluded a seven-year flight to the nearby asteroid 25143 Itokawa. While it's still unknown if the spacecraft managed to capture samples on its trip, the fact remains that this approach may very well be the only valid one in accurately confirming various scientific theories concerning a wide array of subjects.

While theoretical studies can easily get to the bottom of an issue, and can also serve to explain why certain phenomena take place, the fact is that they are still subjected to error and doubt. An easy way to disprove such a study is to go out and collect data from the source. While this is not always possible – for instance, a probe sent to a black hole for sample retrieval would most likely never return – in some cases it is. This is why space agencies around the world are dedicating their resources to developing viable sample-return missions.

The benefits of such an endeavor clearly outweigh the risks and costs involved, experts believe. “With a sample-return mission, you have a resource from which you can harvest information for generations. It is much easier and more efficient to perform analyses on Earth than anywhere else,” expert Michael Zolensky explains. The expert, who holds an appointment at the NASA Johnson Space Center, in Houston, Texas, is in charge of curating some of the first interplanetary dust samples, collected by the American space agency's Stardust mission.

“We get much more precise data off of returned samples. You can have a sample and test it with different state-of-the-art instruments, and different teams can confirm or dispute the results. People have been looking at the sun with remote sensing, but they're not anywhere near close to the accuracy and precision that you can get with a return sample,” Judith Allton, curator of the Genesis solar-wind sample, adds. The NASA Genesis spacecraft launched in 2001, and managed to successfully collect particles from solar winds.

But perhaps one of the fields that could benefit the most from sample-return missions is planetary exploration. This catches on new meaning when considering Mars or Venus. “There are some things we can't do on Mars – dating a rock is one of the critical things. We know that water was a critical part of the planet's history, but we won't know for how long until we can date some of the rocks,” NASA Headquarters Mars chief scientist Michael Meyer concludes, quoted by Space.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //