As scientific instruments become more sensitive to measurements, the accuracy of scientific studies increases as well. But more precision equals more questions, as issues that had once been concealed by the lack of proper equipment are now starting to show and challenge existing theories. One such instance is represented by the gravitational anomalies certain areas of the planet exhibit, for which researchers have been struggling hard to find explanations. In a recent study, a group of experts proposes a new idea to explain these gravitational inconsistencies, Wired reports.

The scientists, based at the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, say that the anomalies are actually triggered by deeply-buried tectonic graveyards. These are places where ancient tectonic plates collided and submerged, moving in depth up to the planet's central core. As this happened, the huge temperatures and pressures present inside the Earth forced the recently-submerged plates to release the water they contained. This had the effect of reducing the density of the rock on top. Given that gravity is directly linked to mass, a lower density equals a lower mass and a lower gravitational pull.

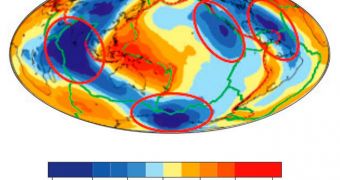

The Caltech group believes that this helps explain why the anomalies are stronger in particular regions of the world, which even today exhibit considerable amounts of tectonic activity. The recent investigation mostly focused on four regions of interest around the globe: the southern parts of Asia, the northeastern Pacific Ocean, the western Atlantic Ocean, as well as an area south of New Zealand, alongside the Antarctic coastlines. The new idea explains with great accuracy the abnormally-low gravitational values registered in these particular regions, the team says.

The work was led by Caltech expert Michael Gurnis, who is also the author of a new paper detailing the findings. The research appears online, in the May 9 issue of the esteemed scientific publication Nature Geoscience. Gurnis explains that the ancient slabs of rock that were submerged in the mantle still linger there to this day, albeit in a dehydrated form. They boost the speed of seismic waves traveling through the magma, as measured by precision equipment. Investigations in these issues are usually done at shallow depths, of no more than 1,000 kilometers.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //