Writing in a recent issue of the journal Nature Nanotechnology, researchers with the Vienna University of Technology document the development of ultra-thin layers of tungsten and selenium that, experiments show, behave like flexible solar cells.

Hence, the scientists who created these layers argue that it might be possible to use the material they are made from, i.e. tungsten diselenide, to coat windows.

The end goal would be to turn them into photovoltaic panels, the scientists who worked on this research project go on to explain.

As specialist Thomas Mueller puts it, “We are envisioning solar cell layers on glass facades, which let part of the light into the building while at the same time creating electricity.”

What's more, the material might even be used to create flexible displays, the scientists theorize.

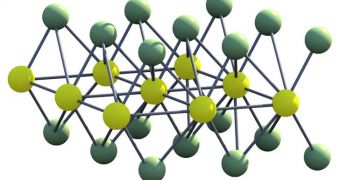

In their paper, the researchers detail that the material they worked with, i.e. tungsten diselenide, owes its name to the fact that it is made up of one layer of tungsten atoms that are connected by selenium atoms above and below the tungsten plane.

By the looks of it, the tungsten diselenide layers that the Vienna University of Technology specialists had the chance to toy with are so thin that, when exposed to light, about 95% of it passes straight through them.

However, evidence indicates that one tenth of the light that the layers absorb can be harvested and converted into electrical power.

The scientists say that, should several more such layers be stacked one on top of the other, it would be possible to absorb more light.

However, if the goal were to be turning windows into photovoltaic panels, thin layers would still work best. This is because they would produce electrical power without blocking visibility.

The scientists expect that their discovery that thin layers of tungsten diselenide can serve as solar cells will help make it easier to harvest sun power.

Thus, they say that these layers could one day replace the standard solar cells that are both inflexible and rather bulky.

What's interesting is that scientist Thomas Muller and his fellow researchers discovered the properties of tungsten diselenide layers while looking for materials that can be arranged in ultra-thin layers just like graphene can, but whose electrical properties are better than the latter's.

“The electronic states in graphene are not very practical for creating photovoltaics,” Thomas Mueller explains his and his colleague's decision to go looking for such materials.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //