According to the conclusions of a new study from experts at the Northwestern University and the University of Chicago, it would appear that super-Earth-class extrasolar planets may share more attributes in common with our planet than researchers were first led to believe.

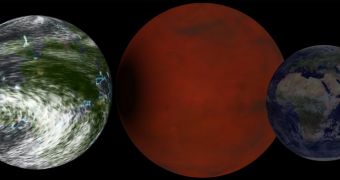

Super-Earths have come under heavy scrutiny lately due to the fact that they resemble our own celestial orb, but at the same time exhibit some crucial differences, such as size and mass. While they are generally larger than Earth, they never exceed the size of ice giants such as Neptune.

Another term to use for these exoplanets is mini-Neptune. In other words, a planet in this group can weigh anywhere between 2 and 15 earthly masses. Many of them could potentially support oceans on their surfaces, if they were found to reside within their parent stars' habitable zones.

The new study, which will also appear in the January 20 print issue of the esteemed Astrophysical Journal, was presented to the scientific community on Tuesday, January 7, at the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), held in Washington, DC.

The investigation was led by postdoctoral astrophysics fellow Nicolas B. Cowan, with the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA) at Northwestern, and University of Chicago assistant professor of geophysical sciences Dorian Abbot.

Their newly-developed model suggests that the climates of super-Earths may resemble our planet's own to a much greater extent than previously hypothesized. Current theories on mini Neptunes suggest that they have very un-Earth-like environments, e! Science News reports.

Previous studies have suggested that these planets are water worlds, where no continents exist due to overflowing, shallow oceanic basins. The new simulation indicates that this is not the case. Cowan and Abbot say that super-Earths most likely have stable climates, and feature both oceans and landmasses.

“Are the surfaces of super-Earths totally dry or covered in water? We tackled this question by applying known geophysics to astronomy. Super-Earths are expected to have deep oceans that will overflow their basins and inundate the entire surface, but we show this logic to be flawed,” Cowan said.

“Terrestrial planets have significant amounts of water in their interior. Super-Earths are likely to have shallow oceans to go along with their shallow ocean basins,” the expert added at the AAS meeting.

The team argues that most of the water on super-Earths is stored within the mantles, but only if the worlds in question still feature an active core capable of supporting plate tectonics.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //