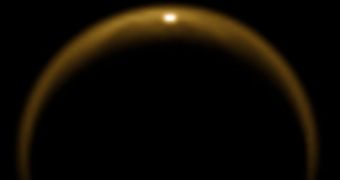

Though the NASA/ESA Cassini spacecraft did a number of flybys around Titan, its advanced instruments were not able to penetrate the cloud layers on the moon, so researchers only had to rely on incomplete data collected by non-visual instruments. Regardless, they were able to infer the existence of lakes of liquid hydrocarbons on the celestial body's surface, and to even draw conclusions on the long-term climate variations that took place on Titan because of them. Now, a new piece of evidence comes to confirm that at least the northern regions are covered in liquid.

The Cassini spacecraft was behind these observations as well. The exception from all other instances was the fact that the probe's instruments managed to catch a glimpse of the reflections caused in the lakes by sunlight. In other words, it was just at the correct position for that to happen. The recent images it sent back serve as definite proof that some liquid exists in the northern regions of Titan, in the lake-shaped basins that dot the area. Similar structures, though fewer in numbers, have also been identified in southern areas as well.

According to experts at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California, the spacecraft has been trying to get a photo of the reflections since 2004, but has been unable to fulfill this part of its mission until now. The photograph it finally sent back will be showcased today, December 18, at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), which is held in San Francisco. “This one image communicates so much about Titan – thick atmosphere, surface lakes and an otherworldliness. It's an unsettling combination of strangeness yet similarity to Earth. This picture is one of Cassini's iconic images,” JPL expert and Cassini project scientist Bob Pappalardo says.

“I was instantly excited because the glint reminded me of an image of our own planet taken from orbit around Earth, showing a reflection of sunlight on an ocean. But we also had to do more work to make sure the glint we were seeing wasn't lightning or an erupting volcano,” expert Katrin Stephan, from the Berlin-based German Aerospace Center (DLR), adds. She is also an associate member of the Cassini visual and infrared mapping spectrometer team and was among the first persons in the world to see the new image, on July 10, 2009.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //