Before Columbus and the Vikings, other sailors could have entered the Americas: the Polynesians. This is strongly suggested by chickens grown by tribes in Peru and Chile, which do not have European ancestry, but Polynesian, but also by some cultural facts common to tribes of the Amazon and Malayo-Polynesians from Indonesia and Pacific, like the use of hammock, blowpipe and the "Big House" of the tribe. And even that common fringed haircut, not found in other cultures and some crops mysteriously cultivated by the Native Americans and in southeastern Asia.

The statues of the Polynesian inhabited Easter Island have some similarities with Andean sculptures. A new research underlines the fact that ancient Polynesians sailed thousands of miles for exploration and trade, supporting the traditional tales of enormous ocean voyages and revealing an ancient trading network between Hawaii and Tahiti about a thousand years ago.

If these skillful sailors traveled throughout the Pacific, the journey to South America by the 1400s A.D would have been a mere trip.

The team at the University of Queensland in Australia investigated 19 stone adzes, collected from nine islands in the Tuamotu Archipelago, located at over 1,000 mi (1,600 km) southeast of Tahiti (eastern Polynesia).

The adzes' stone was basalt, a volcanic rock absent from the Tuamotus, thus the tools must have entered the islands before the arrival of the Europeans in the area. The isotopes analysis of the basalt located its sources in islands like Pitcairn and the Marquesas. But the C7727 adze, coming from the tiny atoll of Napuka was made from the fine-grained basalt type named hawaiite, unique to the Hawaiian island Kaho'olawe, found 2,500 mi (4,000 km) to the northwest of Napuka, along the coasts of the Western Europe.

"Until our discovery, there was no object found in southeast Polynesia that we could link back to a source in Hawaii. The findings corroborate Hawaiian oral tradition that recounts canoe journeys over the vast southeastern Pacific-the last region on Earth colonized by humans. This 4,000-kilometer [2,500-mile] journey now stands as the longest uninterrupted maritime voyage in human prehistory", said co-author Kenneth Collerson. This also corresponds to a "pulse of migration into southeast Polynesia about 900 A.D.", Collerson added.

The stones could have been collected before the departure as canoe ballast, and probably transformed into tools or later offered as gifts to remote trading partners. "The Tuamotu group was likely a center of trade. It was probably the Singapore of the Pacific." said Collerson.

This clearly shows that early Polynesian journeys were not accidental. "Rather, the journeys were carefully planned and skillfully conducted, with a thorough understanding of the geography of island archipelagoes." said Ben Finney, a professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Hawaii.

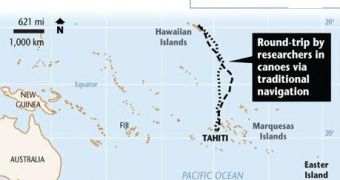

In 1976, Finney together with a Polynesian crew remade the route in a traditional twin-hulled canoe from Hawaii to Tahiti and back, based just on traditional navigation techniques, like star reading, wind compasses, observing migrating birds' behavior, and keeping a bearing relative to prevailing sea swells. "Such voyages would initially have been exploratory, and canoes would have been laden with tools, provisions, and a crew of men and women carefully selected to establish new colonies," said Finney.

The journeys could have been scheduled for catching the favorable trade winds, easing the return voyage. "I'm delighted that [Collerson and Weisler] are at last getting some hard evidence for us. We can now get a handle on back-and-forth voyaging. The challenge now lies in determining the true extent of Polynesian colonization. Now that we've found a chicken bone in South America, the job is to find those adzes.", said Finney.

The novel analysis techniques have "opened up a Pandora's box of opportunities. We can now track down [the source of stone artifacts] throughout Polynesia.", said Collerson.

"But further mysteries about the Polynesians remain. While navigational knowledge would have grown as it passed down through hundreds of generations, voyaging in the southeastern Pacific mysteriously ended around A.D. 1450. Perhaps that knowledge was lost or climate change influenced weather patterns that made sailing more difficult.", he added.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //