In a study whose conclusions could be used to develop new approaches for addressing obesity and diabetes, researchers at the University of California in Berkeley (UCB) found that adult stem cells are capable of reshaping human organs.

This ability allows the body to adapt to changes in the body and the environment. The research team says that this study is one of the first to demonstrate that stem cells do not remain in a fixed state throughout an individual's life.

Until now, experts widely believed that stem cells remained the same after they reached maturity, lining tissues and organ walls, and replacing dead cells as the need arose. But this study demonstrates that adult stem cells are also capable of modifying the very shape of organs such as the gut.

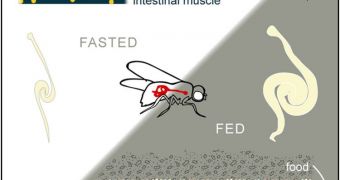

In an experiment conducted on fruit flies, researchers determined that increased food intake caused adult stem cells in the insects' guts to produce more intestinal cells. Through this mechanism, the size of the flies' intestines increased to accommodate the added volume of food they were ingesting.

UCB expert Lucy O’Brien says that intestinal insulin cells appear to be the ones who sent the signals necessary to cause an increase in gut size. The same type of cells are present in mammals as well, including humans. This makes experts believe that the findings could also be applicable to us.

“When flies start to eat, the intestinal stem cells go into overdrive, and the gut expands. Four days later, the gut is four times bigger than before, but when food is taken away, the gut slims down,” says O'Brien, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the university.

“Because of the many similarities between the fruit fly and the human, the discovery may hold a key to understanding how human organs adapt to environmental change,” UCB associate professor of molecular and cell biology David Bilder adds.

The team published the full results of its experiments in the October 28 issue of the esteemed medical journal Cell.

Such investigations “could provide important insights into the therapeutic use of stem cells for treatment of different gastrointestinal and metabolic disorders such as diabetes,” Abby Sarka and Konrad Hochedlinger comment.

The two researchers – who are based at the Harvard University – were not a part of the investigation. They published their opinions in a commentary accompanying the Cell paper.

The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Genentech Foundation Fellowship of the Life Sciences Research Foundation funded the new investigation.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //