In an achievement that is bound to raise the bar for other researchers in the field as well, experts at the Boston University have recently developed the first completely wireless brain-computer interface. The system is groundbreaking, as it works by converting brain waves in FM waves, which are then decoded to produce the sounds that patients unable to vocalize want to express. At this point, test participants using the new system are only able to synthesize vowels accurately, which is less than what can be achieved with wired BCI. But experts say that future developments may see the interface become more efficient.

“All the groups working on BCIs are working toward wireless solutions. They are very superior,” BU cognitive scientist Frank Guenther explains. The expert has been a part of the team that has helped develop the new wireless BCI, which is currently being tried out by Erik Ramsey. The 26-year-old got into a very nasty car accident more than ten years ago, and is currently severely paralyzed. Though still in its infancy, the brain-computer interface technology is currently being used for a variety of purposes, including to send text messages, to drive wheelchairs, and even to Tweet.

In fact, an entire new field dedicated to BCI ethics emerged. Experts handling this ask questions such as what happens when healthy people decide to get them, or how the new networks will be protected from hacking. There is no telling what kind of consequences we would be looking at if the wheelchair of a patient was hijacked electronically and driven as the attacker pleased. These scenarios are admittedly some distance away, but progress is moving fast. BCI moved from speculation to infant technology in less than ten years, Wired reports.

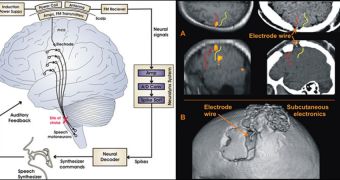

In a paper published in this Wednesday's issue of the open-access journal Public Library of Science ONE, experts reveal that the new system works by having electrodes implanted directly into the brain of a patient. This allows for a faster pick-up of electrical impulses in neurons, and for a faster conversion into FM waves too. “The system produces the sound output in about 50 milliseconds. That’s the time it takes for sound output to come from a motor cortex command in a normal individual,” the scientist explains. Plans are to add even more electrodes to Ramsey's brain, perhaps as many as 32, so as to ensure that consonants can be uttered as well.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //