The fact that billions upon billions of bacteria live in the human gut is no longer a secret. Without these symbiotic microorganisms, we would most likely die right away, due to our inability to process nutrients without them. Now, researchers have managed to figure out how the intestines protect themselves against harmful species of bacteria that inevitably make their way inside our guts.

What researchers at the Yale University, the University of British Columbia, and the Weizmann Institute of Science discovered is very worrying – apparently, a single gene regulates the immune system defenses responsible for not allowing dangerous microorganisms to permeate our cells.

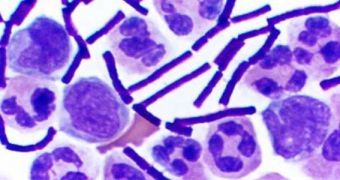

This molecular switch governs the production of a thin protective mucus that lines the insides of our intestines. This mucus has often been likened to a demilitarized zone, where no immune cells and bacteria exist. Now, experts are uncovering just how sensitive these defenses can be, especially in the face of threats capable of modifying genetic code.

Until now, scientists did not know that the immune system regulator NLRP6 inflammasome was the only gene responsible for the production of this shield. According to the research team, this switch works just like a faucet, allowing for more or less of the mucus to be produced, as needed.

“This gut microbiota has been linked to the inflammation that triggers obesity, diabetes, metabolic disease, and most of chronic health problems of the Western World. We knew these invaders were causing problems, but we didn’t know how,” says researcher Richard Flavell.

The expert holds an appointment as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and is also the Sterling professor of immunobiology at the Yale University. He was the co-senior author of a new study detailing the findings, published on February 27 in the journal Cell.

In a series of experiments, the team determined that mouse models that featured a silenced version of this gene did not display their mucus shields in the gut. As such, they became prone to infections and inflammation, and developed diseases ranging from type II diabetes and colon cancer to fatty liver disease and inflammatory bowel diseases.

“The next step is to identify the bacteria in humans, prove that the system works the same way it does in mice, and figure out how to dial up the protective shield,” Flavell explains. He led the work with WIS colleague Eran Elinav and UBC investigator B Brett Finlay.

The investigation was supported by the HHMI, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the US Department of Defense, the Blavatnik Family Foundation, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, European Research Council, and the Israel Science Foundation.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //