A paper published in a recent issue of the top journal Science reiterated the necessity of global and frequent data coverage of volcanoes. This can be achieved by using satellites. Various spacecraft have already begun revealing signs that once-dormant volcanoes start to reawaken.

To put things into perspective, it's important to note that most volcanoes in the world are not under constant monitoring. The majority of those who are being surveyed are only partially covered. Only the largest, most active volcanoes have dedicated observatories keeping track of their activities.

In the Science paper, entitled “Monitoring Volcanoes,” experts analyze the situation of over 440 active volcanoes, spread over 16 developing countries, mostly in Africa. They found inappropriate or no monitoring for 384 of these mountains.

Of this group, 65 volcanoes were classified as being potentially dangerous for significant populations, and for extensive land surfaces. Many of these mountains were located on remote and inaccessible terrain, which contribute to making monitoring efforts very difficult.

The global perspectives that satellite systems enable therefore become extremely important, officials with the European Space Agency (ESA) believe. Spacecraft such as the flagship Envisat Earth-monitoring satellite can be used to detect unrest or build-up activities in unmonitored volcanoes.

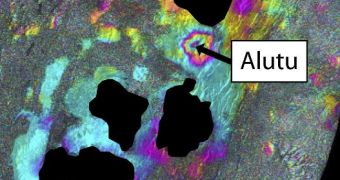

Envisat can use a remote-sensing technique called Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) to detect these activities. The approach works by snapping radar images of a location from several different angles, and then combining them into a single dataset.

“Tiny changes on the ground cause changes in the radar signal and lead to rainbow-coloured interference patterns in the combined image, known as a ‘SAR interferogram,” an ESA press release says.

“Movement of magma underground may cause deformation of the surface above, thus InSAR can be used to monitor volcanoes. Active volcanoes are often dangerous and difficult to access, so satellite methods provide a global perspective not achievable using ground instruments,” the statement adds.

According to investigators, this remote-sensing technique is extremely well suited for conducting observations over areas where cloud covers prevent direct observations through other methods. This is especially true for tropical areas.

“Satellite views also provide a global perspective, mapping tectonic strain across continents and allowing the exploration of volcanoes in remote or inaccessible areas,” ESA scientists explain.

“As a result, many volcanoes previously thought to be dormant are now known to be showing signs of unrest. The resources for acquiring more detailed, ground-based monitoring can now be targeted at such volcanoes,” they conclude.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //