The Hawaiian Archipelago, more precisely its Leeward side, is the perfect place to construct a renewable energy power plant, experts say. According to a new series of studies, this is the ideal location to construct facilities that rely on the ocean's seawater to drive impressively large turbines. These heat engines would steadily produce electricity, and would cost very little to operate. The cost of maintaining them would however be pretty high, critics say.

The new report was produced by a team of investigators based at the University of Hawaii in Manoa (UHM). The group investigated the Leeward side of the Hawaii Islands closely, and determined that the region could contain not one, but several such installations. The technology that are proposing be used is called Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC), and the group describes it more closely in the latest issue of the esteemed scientific Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy. The magazine is published by the American Institute of Physics (AIP), e! Science News reports.

“Testing that was done in the 1980s clearly demonstrates the feasibility of this technology. Now it's just a matter of paying for it,” says of the proposal Gerard Nihous, who is based at the UHM. He explains that some of the greatest challenges associated with opening up such advanced power planets are high costs and reduced efficiency. This is why his area of expertise is improving estimates for both these factors, so that OTEC facilities become possible, and also desirable. Thus far, Nihous' work has only remained theoretical, but the conclusions of his studies are very promising.

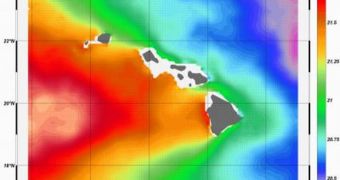

In order to produce the new study, the expert and his team looked at data supplied by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The group learned that NOAA National Oceanographic Data Center (NODC) readings seem to point at the western side of the Islands as the promising location for OTEC power plants. It is here that temperature differences in the seawater are significant enough to create the kind of effect these facilities need to produce important amounts of electrical current. The warm-cold temperature differential is apparently 1 degree Celsius larger in western Hawaii than in the eastern part of the island, the team says.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //