European researchers recently participated in the Fringe Workshop, a meeting organized at the European Space Agency's (ESA) Center of Earth observation (ESRIN), in Frascati, Italy. At the conference, they shows that satellites can detect subsidence of just a few millimeters.

Subsidence is a term used in geology to refer to downward ground movements. A comparable word would be sinking, although the latter is an active process, whereas the former is passive. The opposite phenomenon to subsidence is ground uplift.

What scientists showed at the workshop is that the most advanced satellites are capable of discovering even the faintest motions of the surface, even from their orbital perches, hundreds of kilometers above the surface of the planet.

The primary technology used for this type of studies is called Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR), and is currently outfitted on just a handful of spacecraft. The study method works by snapping multiple images of the same location, and then analyzing the differences between them.

By applying this approach to studies on the Italian city of Assisi, researchers established that some parts of the town are sinking by as much as 7.5 millimeters (0.29 inches) per year. These results were presented at the meeting as well.

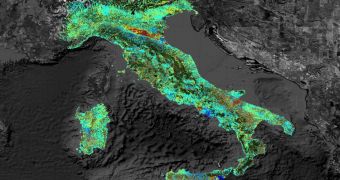

“Tiny changes on the ground cause changes in the radar signal and lead to rainbow-colored interference patterns in the combined image, known as ‘a SAR interferogram.’ The Fringe Workshop takes its name from these colored fringes seen in the interferograms,” an ESA press release explains.

Some of the phenomena that InSAR can detect include the so-called breathing of active volcanoes, the thermal expansion of human buildings during very hot days, the movement of tectonic plates past each other, and even the effects of draining an underground aquifer on the streets above.

When the technique was first developed, it could only be applied to narrow areas, and the effort required to do so was painstaking. Now, due to technological advancements, it is possible to image areas as large as Italy at very high resolution levels.

“Tracking surface changes is important for areas like this because it is home to an oil reservoir. While the now-retired ERS satellites played a major role in advancing interferometry, radars aboard satellites such as ESA’s Envisat continue to collect data used to detect surface changes,” the ESA statement adds.

“The Sentinel-1 satellite due to be launched in 2013 will ensure the continuity of SAR data for years to come, with improved coverage compared to its ERS and Envisat predecessors,” the document concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //