Solar physicists at the American space agency say that their Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) spacecraft were able to follow the path of a coronal mass ejection (CME), from origins all the way to the time when it reached our planet.

In part, the creation of the dataset was enabled by the fact that investigators now have access to new data processing techniques, which enable them to stitch spacecraft observations together seamlessly.

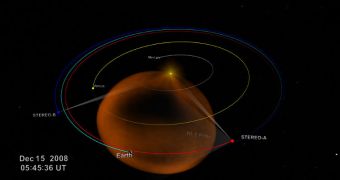

In addition, the STEREO twin space probes are unique. One of the them moves ahead of our planet in a heliocentric orbit, while the other trails behind. This provides experts with a 3D (stereo) image of the Sun. In some configurations, this system can reveal the entire surface of the star at once.

The probes' main mission is to study how solar storms of all types, shapes and sizes are triggered, evolve and develop over time. The massive amounts of radiation that the Sun emits can be very dangerous for astronauts in orbit, power grids, satellites, and other electrical instruments.

Though STEREO has been improving physicists' ability to predict how CME will behave since 2006, researchers still could not know for sure where the radiation would hit and when. The best they could do was create predictive models.

Recently, with the aid of the aforementioned data processing techniques, solar physicists were able to piece together a clip showing how the radiation and material released from the Sun during a CME traveled through the solar system until they reached Earth.

This allowed investigators to determine what factors most influence the particle cloud, and to what extent. In the future, these data will be used to make better predictions of where a solar storm would hit, and what its effects might be.

“The clarity these new images provide will improve the observational inputs into space weather models for better forecasting,” NASA Headquarters STEREO program scientist Lika Guhathakurta explains. She says that the CME STEREO collected data for took place back in 2008.

Details of the new investigation appear in a paper published in the August 18 issue of the esteemed Astrophysical Journal. The lead author of the work was scientist Craig DeFores, who is based at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), in Boulder, Colorado.

“Until quite recently, spacecraft could see CME only when they were still quite close to the Sun. By calculating a CME's speed during this brief period, we were able to estimate when it would reach Earth,” says Alysha Reinard.

The expert holds an appointment with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center. After the first few hours, however, the CME would leave this field of view and after that we were 'in the dark' about its progress,” she adds.

“The ability to track a cloud continuously from the Sun to Earth is a big improvement. In the past, our very best predictions of CME arrival times had uncertainties of plus or minus 4 hours. The kind of movies we've seen today could significantly reduce the error bars,” the expert concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //