A pair of identical spacecraft launched back in 2006 was recently used to scan the skies in search for binary star systems. The observatories proved extremely efficient at this, identifying no less than 122 such paired stars, astronomers say.

The researchers, based at the University of Central Lancashire, in the United Kingdom, took advantage of the capabilities provided by the NASA Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) probes in order to conduct this research.

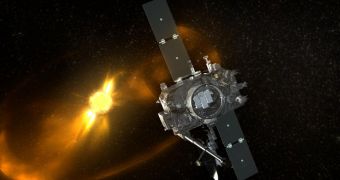

Launched on October 26, 2006, the twin probes are different from other solar observatories in that one of them moves ahead of our planet in orbit, while the other lags behind. This provides a stereoscopic, 3D view of the Sun, and of events taking place on its surface.

Over the course of its mission, STEREO provided solar physicists with new insights into how the Sun functions, but also managed to complete some extracurricular activities on the side, such as for example detecting a few comets in the inner solar system.

Recently, experts in the UK figured out that the probes' sensitive detectors were able to find binary star systems, by analyzing subtle changes in the brightness of stars, as their companions passed between them and the observatories.

These data were collected using the heliospheric imagers the two spacecraft carry. In 4 years and 7 months of continuous mission, STEREO photographed no less than 900,000 background stars.

“We've used the stars to calibrate the instruments. Because our calibration has been made to a high standard, [we] knew that we could subsequently do science with the background stars,” Lancashire expert Danielle Bewsher said in an email interview with Space.

Experts at the university now say that analyzing the data that STEREO produced in even more depth could reveal more signs of binary star systems across the background. However, this is a very tedious task, that requires a lot of attention and patience.

“Eclipsing binaries [EB] allow for more detailed studies of their host stars. A catalog of bright EB amenable to follow-up observations would therefore be very useful to a wide range of astronomers,” Bewsher explains.

Details of the new study will be detailed in an upcoming issue of the esteemed scientific journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //