As a major crisis is unfolding in the Horn of Africa, the European Space Agency (ESA) is keeping tabs on the situation from orbit. The organization uses its satellites to track how more and more vegetation is destroyed daily, while precipitations stubbornly refuse to fall.

Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia and Djibouti are the most affected African states. Already, the drought that has been plaguing the region for months has driven several tens of thousands of people from their homes, and into exile.

Even before the natural catastrophe, the area faced monumental food insecurities, but now the situation is quickly degenerating. The crisis is visible for space, but it's a lot more present in the minds of people on the ground, who did not have too much to begin with.

SMOS data are revealing a troublesome picture – soils in the affected areas are now simply too dry to allow for any type of edible plant to grow. This is also visible in the number of refugees making their way to specialized camps acorss the region.

At the Dadaab refugee camp, in Kenya, social worker admit more than 1,000 new people daily, most of which are extremely dehydrated and malnourished children. The situation is especially worse for Somali refugees, seeing how their country is also at war.

International aid agencies unanimously agree that this is the worst drought to hit the area in decades. This is one of the reasons why ESA become involved with aiding the relief effort. It is using the Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity satellite for the job.

The instrument, launched on November 2, 2009, is an Earth-sensing spacecraft that is part of the ESA Living Planet Program. Its goal is to study the world's water cycle, and also to measure moisture in soils across the globe.

Some of its detectors are specifically designed to measure oceanic salinity, a measure that determines how much evaporation will occur at any time over a given area. These datasets are absolutely essential for understanding the planetary water cycle.

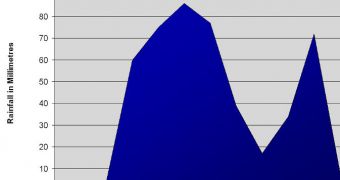

During this year's main rainy season, the satellite showed no significant changes in soils at the Horn of Africa. This was usually the time of area when the region got its precipitations. As it stands, no water was trapped in the soil, and a major drought ensued.

“The SMOS measurements in such areas are probably two to four times more accurate than those with other satellite sensors or models,” SMOS soil moisture lead scientist Yann Kerr explains.

The expert is based at the CESBIO center for studying Earth’s biosphere from space, in Toulouse, France.

“Although the country’s proximity to the equator means there is not much seasonal variation in climate, the April to June rains are important for agriculture,” an ESA press release concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //