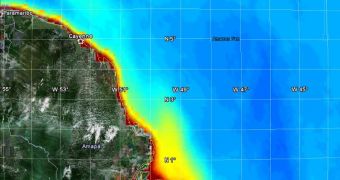

The SMOS satellite has just beamed back new data on the planet's water cycle, experts at ESA announce. They say that the preliminary data looks at how surface currents affect the 'Amazon plume'.

The goal of the investigation was to see how the plume disperses into the open sea, and to identify and analyze the factors that influence its spread.

Observations the satellite conducted of the plumes are the latest in a series of studies. It has been delivering observations of 'brightness temperature' since mid-July.

With the new data, the Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity spacecraft demonstrates once again that it has what it takes to conduct highly-detailed observations of the way heat and water move on Earth.

Based on the frequency of data that the satellite has beamed back this far, experts at the European Space Agency (ESA) say that they are able to produce global maps of soil moisture once every 3 days.

Additionally, maps of ocean salinity can be compiled once every month at least. With these datasets, the spacecraft helps us improve climate and weather models, for more accurate predictions.

Especially sensitive to the information that SMOS can supply are agriculture and water resource management, which could both use warnings of the kind this mission can provide.

“One of the dramatic steps forward achieved with SMOS is that we now have the ability to track the movement of low-salinity surface waters, particularly those resulting from large 'plumes' such as the Amazon,” says Ifremer expert Nicolas Reul.

“Observations between mid-July and mid-August clearly show how the North Brazilian Current transports fresh water from the Amazon River as the current flows across the mouth of the river,” the scientist adds.

“These observations confirm the excellence of the data we are already getting from SMOS,” he says.

Reul says that the Amazon plume accounts for no less than 15 percent of the total input of fresh water the world's oceans receive every year.

The Plume has been observed continuously over the past few weeks. The researchers discovered that it tends to curve back on itself around this time of year, under the influence of the North Brazilian Current.

“At the same time, the Orinoco plume has also been clearly visible as a tongue of fresh water entering the Tropical Atlantic along the windward side of the Caribbean islands,” the expert says.

“These observations are a good example of how well SMOS is performing and they show us that the mission can provide data on temporal sea-surface variability at scales of less than a week,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //