A team of researchers led by Channing Der, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Pharmacology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, carried out a new study on pancreatic cancer, and the very simple organism they focused on, led them to an amazing discovery.

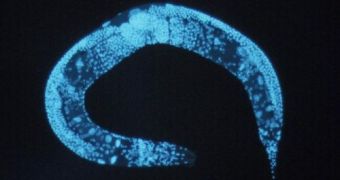

Caenorhabditis elegans – the common roundworm, allowed them to see the way that the Ras oncogene chooses a signaling pathway and what are the consequences of that choice in cellular development.

This is a crucial issue in cancer, since it is a disease characterized by uncontrolled cell growth.

The scientists chose the roundworm because despite all the advances in genetic science, showing that the Ras oncogene is mutated in most pancreatic cancers, the signaling pathways in humans are far too complex, making it very difficult to identify potential therapeutic targets.

“In humans the cell signaling pathways are very complex; there are more than 20 different downstream partners beyond the two proteins we study – Raf and RalGEF – that Ras can choose to interact with,” explains Der, who is also a member of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“In C. elegans, there is only one of each protein,” and “that made it easier for us to identify how Ras chooses a partner to ‘dance’ with and what are the critical events in the subsequent cell development that promote cancer.

“We found an elegant mechanism by which Ras switches partners and showed that the choice leads to very different fates for the cell.

“Now we can go back to the human pancreatic cancer cell and ask whether similar mechanisms are at work in determining how Ras causes pancreatic cancer,” he adds.

It is very frequent that scientists use a simpler organism for their studies, in order to better observe a genetic and cellular activity that would practically be impossible to study in detail in humans.

“Worms’ cells actually share a great deal of functional overlap with human cells,” Der said.

“However, while there may be one mechanism in a simple organism like a worm, there are multiple mechanisms at work in humans.

“It’s a great thing for us as people, because there is a great deal of redundancy in our biological systems that helps them self-repair and function better, but it makes it a lot harder to study what’s going on at a basic level.

“If this signaling works in a similar way in humans, the C. elegans model may be very powerful for helping us find new therapeutic targets for pancreatic cancer,” he concluded.

According to the National Cancer Institute estimates, there are over 43,000 Americans who were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer last year and more than 36,000 died from the disease.

Besides Der, the research team included graduate student Tanya Zand and Assistant Professor David Reiner, PhD, both of UNC’s Department of Pharmacology.

The project was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and it was published in the Cell Press journal Developmental Cell.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //