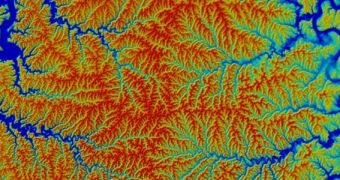

A scientific paper published in the March 6 issue of the top journal Science highlights a new technique for reconstructing ancient landscapes, which relies on analysis of river topographies. Experts at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich say this approach can be very accurate if applied properly.

The group argues that the topography of river basins can be used as both a window into the past and as a predictions tool for the future. The reasons why landscapes change constantly over time are numerous, including erosion, glacier advancements and ice ages, earthquakes, volcanoes, and so on.

By analyzing how river boundaries change over time, scientists can recreate landscape geometries that have not existed on our planet in millions of years. This statistical method is the first of its kind ever developed, and thus far its performances are on par with expectations, Nature News reports.

SFIT researchers explain that their technique works based on estimates of how stable the boundaries or edges of river watersheds are. The method also takes into account the likelihood of watersheds cannibalizing neighboring water basins, a process that promotes erosion and changes the landscape.

“This is an exciting new way to look at topography and back out its history. [These researchers] have put together the principles for running the film backwards,” comments University of Washington in Seattle (UWS) geomorphologist David Montgomery, who was not a part of the research team.

The new study was led by geophysicist Sean Willett. He explains that there are many factors controlling the erosion rates at which rivers go through a certain landscape. Some of these aspects include the inclination of the terrain and the hardness of its rocks, as well as the volume of water and debris that the river carries.

Over time, the expert adds, the natural tendency of a watershed is to grow and become more stable. Its network of tributaries will continuously accumulate new lands, until eventually a stable configuration is reached. The new model can reverse this trend, until the original state of the landscape is determined.

This statistical approach also takes into account a few simple rules about rivers, such as the fact that little ones are steep, whereas their larger brethren are not. Additionally, no river “likes” to be long and skinny, preferring a wider and shorter flow. These natural tendencies also play a role in how the new model reconstructs long-lost landscapes.

This approach is therefore “a great tool for understanding current landscapes in terms of what has happened to them previously,” comments Arizona State University geomorphologist Kelin Whipple, who was not a part of the investigation.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //