In a groundbreaking new investigation, researchers learned that the human brain is capable of recognizing things faster if it knows what it's about to see. In other words, if it has seen a thing before, it's more likely to recognize it faster.

The new discovery goes against established knowledge of how the brain functions. Until now, experts believed that the thought processes leading up to recognition entered consciousness in pretty much the same way at all times.

Simply put, they thought that recognition patterns were rigid. It would now appear that conscious perception is a lot more flexible than that. It can vary depending on the thing a person looks at.

Despite being one of the most complex structures in the entire Universe, the human brain still needs time to process the visual information it receives from the retina. It takes about several hundred milliseconds for data to be correctly processed, and then relayed to other areas of the brain.

But that time can be reduced if the visual cortex is processing data about an object it has seen before. This happens because the brain contains a number of processing stages, in which each of the stimuli produced by the retina gets analyzed in a particular way.

Conscious perception is reached only after the stimuli pass through several of these processing steps, and this takes around 300 milliseconds, PsychCentral reports.

But the team that conducted the new investigation was able to demonstrate that the entire process of perceiving visual information can vary significantly among individuals, based on the number and type of their past contacts with the objects in question.

In experiments conducted by the group, participants were asked to look at a sequence of images showing dots, which gradually became increasingly organized to form a word. Then they were asked to look at the same sequence of images backwards.

The new study was led by experts at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research. in Frankfurt, Germany. “Expectations based on previously acquired information apparently help to perceive the object consciously,” says study first author Dr. Lucia Melloni.

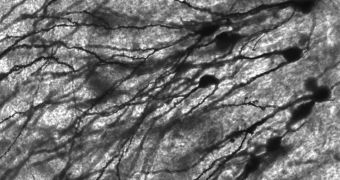

While the test subjects were undergoing this assessment, they were hooked up to an electroencephalography (EEG) machine, which measured the electrical activity of neurons right beneath the skull.

“Our research explains this variability in timing. Apparently, the brain does not process the stimuli rigidly and at the same speed; rather, it is flexible,” explains the director of the MPI Department for Neurophysiology, Dr. Wolf Singer.

“Since the interpretation depends heavily on the sequence of events, EEG activity may have been incorrectly allocated to consciousness processes. In light of these results, it appears necessary to re-investigate the neuronal correlates of consciousness,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //