A group of investigators from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the Edinburgh University announces the discovery of a set of proteins that is believed to play a role in the development of over 130 brain disorders. The study may also clear up some aspects related to the evolution of the brain.

According to official statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO), mental disabilities are on the rise in the developed world, and they already exert a huge pressure on international healthcare systems. In the US alone, these conditions require $300 billion per year.

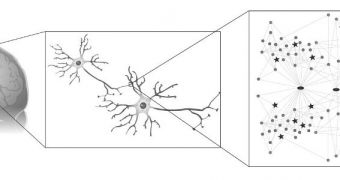

Treating neural malfunctions is a tremendously complex task, given that the brain is the most complex organ in the human body. It features billion of nerve cells, which have trillions of connections to each other. These ties are called synapses.

Each of them contains various protein sets, which combine in a variety of ways to create the postsynaptic density (PSD), a molecular machine whose role in humans is not well known.

Past PSD studies carried out on unsuspecting animal models have revealed however that the molecular machine may play an important role in human diseases and behavior.

Using an investigations method called proteomics, the research group analyzed PSD samples taken from the brains of patients undergoing brain surgery.

The group discovered that synapses contain as much as 1461 proteins, each of which is encoded by a different gene. This provided experts with a new way to study the evolution of the brain and behavior.

“We found that over 130 brain diseases involve the PSD – far more than expected,” explains professor Seth Grant, who holds joint appointments at both institutions.

“These diseases include common debilitating diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders as well as epilepsies and childhood developmental diseases including forms of autism and learning disability,” he adds.

“Our findings have shown that the human PSD is at center stage of a large range of human diseases affecting many millions of people,” the expert argues.

“Rather than 'rounding up the usual suspects', we now have a comprehensive molecular playlist of 1,000 suspects,” adds Jeffrey L Noebels, a professor of neurology, neuroscience and human genetics at the Baylor College of Medicine.

“Every seventh protein in this line-up is involved in a known clinical disorder, and over half of them are repeat offenders,” the expert reveals.

This investigation was conducted as part of the Genes to Cognition Program by three research groups in the United Kingdom.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //