A wide array of drugs used in modern therapies are target-specific, meaning that they only have an effect if they are delivered to a certain location inside the body. But doing this is a very tricky business. Though it allowed itself to get infected once, the immune system is not willing to do the same over and over again, and so it ruthlessly attacks everything inserted into the blood stream, including the drugs meant to help it. A startup company now plans to make drugs more resistant to immune actions, which could drastically increase their chances of success, Technology Review reports.

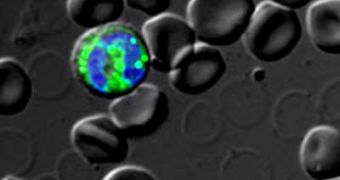

The Stanford University-based company does not plan to create an entire new breed of drugs, but rather to chemically alter existing ones, so as to make them less susceptible to the action of red and white blood cells. The big plan is to laden the drugs with various molecules that would help them bind to the inside of cells, hitching a ride outside the reach of the immune system. Additional molecules will also be added on the surface of existing drugs to boost their abilities of binding to specific sick cells around the body. Each disease creates its own biomarkers, and drugs to follow these markers to their origins are well on their way.

This line of research could lead to drugs with longer half lives, which are the amount of time they endure within our bodies before they are eliminated. The team has already demonstrated the technology with a protease inhibitor, a drug regularly used to fight HIV in infected patients. “We're hoping this will be quite generally useful. One of the things I like about this approach is the combinatorial nature of the synthesis of the molecules,” says SU biologist Gerald Crabtree. His lab hosted the initial work that led to the formation of the company, Amplyx Pharmaceuticals.

“We wondered if we could generalize [our research] to a way of increasing stability for many drugs with problematic pharmacology, which can make them unusable or inconvenient to take. Some drugs have to be taken five times per day, which in turn leads to patient compliance issues,” the expert adds. “Red blood cells have a lot of the binding proteins, so the drug binds tightly to them and slowly leaches out of blood cells,” concludes University of Michigan biologist and Amplyx collaborator Jason Gestwicki.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //