On April 3, at 11:54 CET, the European Space Agency's (ESA) small solar observatory Proba-2 observed a solar eruption taking place on the surface of the Sun. Astrophysicists classified the phenomenon as a low-intensity, or weak, event, even if this still implies temperatures averaging tens of millions of degrees Celsius. Though the event was of reduced intensity, it caused a massive front of charged particles, which headed straight for the Earth. The solar coronal mass ejection (CME) took place as the two celestial bodies were aligned, astronomers reveal.

Generally, solar flares are triggered by sudden impulsive releases of magnetic energy. When this happens, one of the most common outcomes is the generation of solar flares, though other phenomena may emerge as well. The recent explosion released about the same amount of energy that the entire planet consumes in a year, which is essentially nothing compared to larger events of the same class. The resulting waves of charged particles (radiation) spread through space at a speed of about 500 kilometers per second, and their vast majority slammed against our atmosphere.

The shock wave struck the Earth on Monday, April 5. Immediately, the charged solar particles were stopped by the magnetosphere, the protective layer of the atmosphere that is in charge with diverting all manner of radiation that would otherwise destroy life on Earth. The particles were led on top of the planet's magnetic lines, and they ended up above the Arctic and Antarctic regions, where they produced remarkably bright and “lively” light shows, called auroras. Counter-intuitively, as these events were unfolding, astrophysicists took a sigh of relief.

This was the largest geomagnetic storm the Sun caused in more than three years. The fact that the star remained quiet for such a long time was of concern to scientists, given that the body should have exited the solar minimum stage of its 11-year cycle two years ago. The fact that it's beginning to show signs of reawakening is good news for physicists. However, such events can have serious repercussions for us. Powerful solar flares can fry transformers, melt power lines, cripple satellites, and also endanger the lives of the permanent, six-astronaut crew aboard the International Space Station (ISS). The new outburst took place as the ISS was occupied by 13 people, including the seven astronauts aboard the space shuttle Discovery.

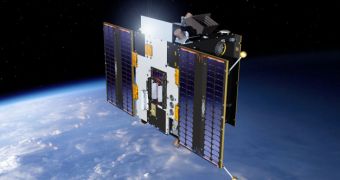

“[The] SWAP [instrument aboard Proba-2] acquired an image every 100 seconds during the flare while SOHO manages one around every 15 minutes. This means we have about 40 images compared to five to six for SOHO, allowing us to see clearly the full range of phenomena associated with such an event,” Royal Observatory of Belgium (ROB) SWAP operations oversight team member David Berghmans says. SOHO is an NASA/ESA mission having kept an eye on the Sun for more than 15 years.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //