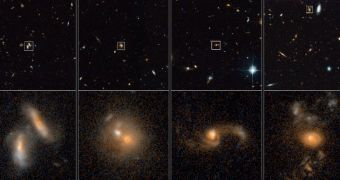

By combining computer models simulating the merger of galaxies with recent studies of archival data collected by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, a team of astronomers was recently able to confirm that previous estimates of galaxy collision and merger rates are correct.

The estimates covered the last 8 to 9 billion years of cosmic evolution. Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is estimated to have began forming about 4.7 billion years after the Big Bang. Experts say that knowing galaxy collision rates is an essential part of understanding how these structures form and evolve.

For example, within the Milky Way, astronomers have already identified remnants of several dwarf galaxies, which collided with our galaxy at different times. The new influx of hydrogen gas stirred up existing clouds here, and new bursts of stellar formation occurred, rejuvenating the galaxy.

The same situation can be encountered throughout the Universe. If astronomers can get a clear picture on how mergers influence overall galactic evolution and interactions, then they will be able to shed more light on what happened in the Universe shortly after the Big Bang.

In past investigations – some of which were conducted using Hubble too – scientists got varying results. Their studies indicate that anywhere between 5 and 25 percent of all galaxies in the early Universe were colliding and merging with each other.

Baltimore, Maryland-based scientists from the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) conducted the new study by analyzing merger rates over time. Team leader Jennifer Lotz says that this was done by looking at mergers taking place at different distances from Earth, all the way to the deep field.

“Having an accurate value for the merger rate is critical because galactic collisions may be a key process that drives galaxy assembly, rapid star formation at early times, and the accretion of gas onto central supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies,” the team leader explains.

In a paper describing the findings – which is published in the October 10 issue of The Astrophysical Journal – the team shows that massive galaxies only merged with each other about once in the past 9 billion years.

However, smaller galaxies had a field day with each other, or with dwarf-sized counterparts. An average of three mergers was found to have taken place for these objects over the same time frame. Lotz explains that the difference between new and old results come from the observation techniques used.

“These different techniques probe mergers at different ‘snapshots’ in time along the merger process. It is a little bit like trying to count car crashes by taking snapshots,” the STScI investigator explains.

“If you look for cars on a collision course, you will only see a few of them. If you count up the number of wrecked cars you see afterwards, you will see many more," the expert adds.

Studies that looked for close pairs of galaxies that appeared ready to collide gave much lower numbers of mergers than those that searched for galaxies with disturbed shapes, evidence that they’re in smashups,” she concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //