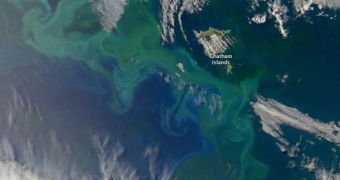

Images snapped with a satellite operated by the American space agency reveal a very large phytoplankton bloom off the coasts of Chatham Island, in New Zealand. This is the time of the year when the annual springtime bloom takes place in this region of the Southern Hemisphere.

The NASA Aqua satellite features an impressive suite of scientific instruments, which allows it to take such images at high resolution, and in exquisite levels of detail.

MODIS (the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) and AMSR-E (the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer-EOS) are the main instruments used for such investigation.

The fact that the phytoplankton bloomed right on cue is nothing but good news for the area. These massive concentrations of microscopic organisms, which are oftentimes visible from Earth's orbit, are the most basic link in the oceanic food chain.

In addition, the plankton is also responsible for taking up vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and storing it until it dies. As this happens, the organisms sink, and take the dangerous greenhouse gas to the bottom of the ocean, where it is deposited.

Without plankton, the ocean would lose it ability to act like a CO2 sponge, and food webs would decay. If these little microorganisms go, then so will the fish that depend on them, and the predators that depend on the fish, and so on.

At this point, experts have not yet observed a diminishing in the number or spread of phytoplankton blooms anywhere in the world. The waters off the coasts of New Zealand are especially highly productive when it comes to such blooms.

This makes the entire area act like a massive natural carbon sink, that traps vast amounts of CO2, removing it from the air. According to experts, the main reason why the area is so productive is the topography of the ocean floor underneath the waves.

Two oceanic currents come together around the Chatham Island, one from the Antarctic flows south of the Chatham Rise (waters are cold, nutrient-rich, but iron-poor), and the other from the north, featuring mostly warm, nutrient-poor, but iron-rich waters.

When the two currents combine, the resulting water in the current provides both the nutrients and iron fertilizers for massive phytoplankton blooms, Our Amazing Planet reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //